Several weeks ago we looked at the phenomenon of population, income, education and unemployment. The impact to from the combination of these factors in certain communities can be difficult. Let’s explore a little further as there is more, interesting data every day. The US Department of Agriculture is releasing its report of rural America. The findings are interesting and counter-intuitive to the understanding of voters in many of those communities. Their findings include:

- The rural areas grew 0.5 % vs 1.6% in urban areas from mid-2011-mid 2012

- Rural incomes are 17% lower than urban incomes.

- The highest income rural works (95th percentile) earn 27% less than their urban counterparts

- 17.7% of rural constituents live in poverty vs 14.5% in urban areas

- 80% of the high poverty rate counties were rural

- All the high income counties are urban.

Wow! So the ghetto has move to the country? According to these statistics there is truth in that statement. Let’s look a little further using some on-line mapping.

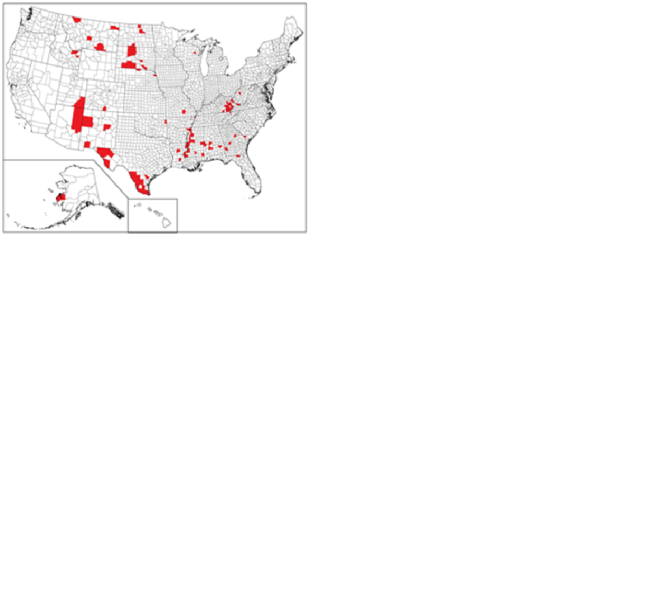

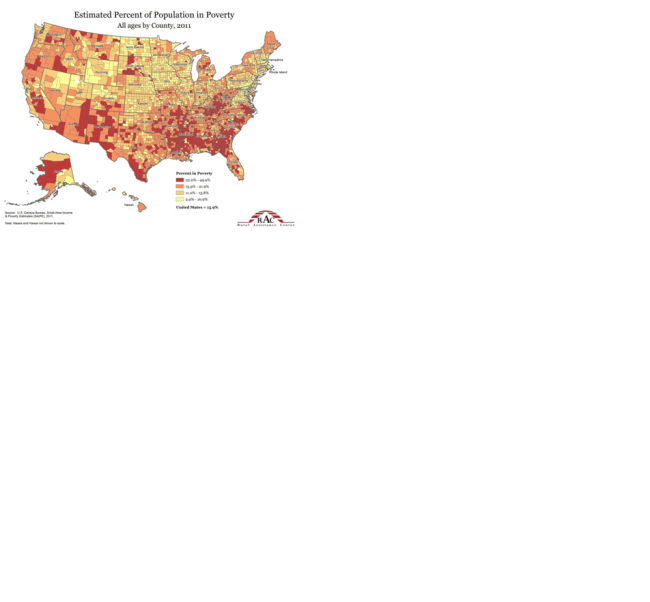

First let’s look at where these rural counties are. Figure 1 is a map from www.dailyyonder.com that shows (in green) the rural counties in the US. Wikipaedia shows the 100 lowest income counties in Figure 2. For the most part, these counties are rural, with the exceptions being a few areas in south Texas and in the Albuquerque/Santa Fe area of New Mexico. Raceonline.com shows the populations in poverty by county. The red areas are the highest poverty rates. The red areas in Figure 3 expand Figure 2 to include much of the rural deep south, Appalachia, more of Texas and New Mexico and part of the central valley in California.

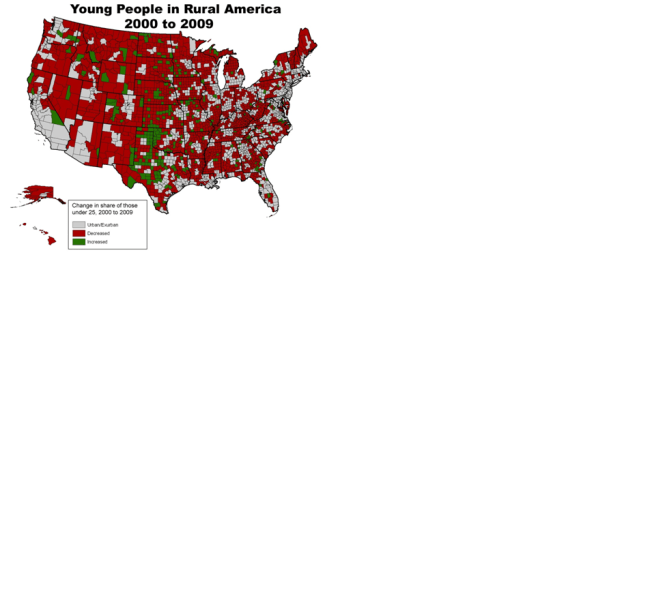

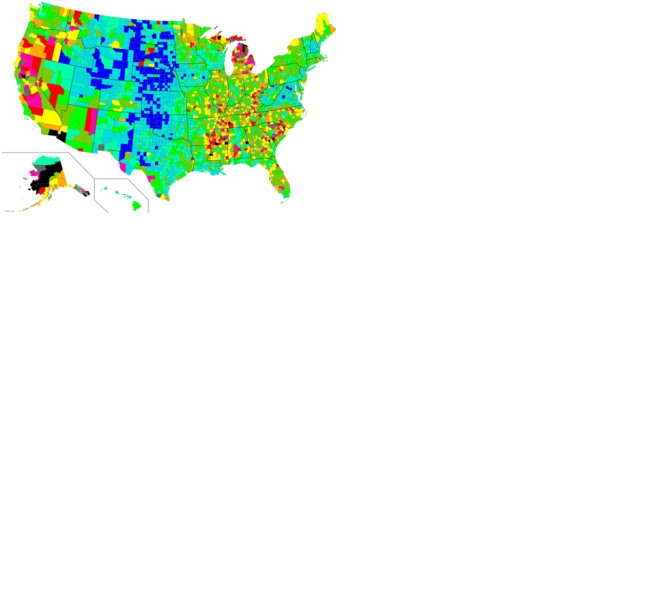

Figure 4 shows how the number of young people has changed between 2000 and 2009 in rural counties (urban counties are white and not included – red means a decrease). Figure 5 shows population growth (or not) by county. What you see in these two maps is that the young people are moving to the rocky mountain states and vacating the high poverty counties in Figure 3. Yong people do not see jobs in the rural area – unemployment is 20% higher in rural America and the jobs that are there pay less. Figures 6 and 7 show unemployment by County in 2008 after the start of the Great Recession and in 2013. What these figures show is that with exception of the Plains states and Rockies, is that many of the areas with high poverty also had high unemployment, and that the unemployment has remains stubbornly high in many rural areas in the Deep South, Appalachia and New Mexico, plus high unemployment in parts to the Great Lakes, but the poverty rates are still lower. Education may by a factor in why the Plains states and Rocky Mountains have less unemployment – despite being rural their students are far more likely to graduate from high school than those in the deep South, Appalachia where unemployment remains high and incomes low.

So what does this possibly have to do with utilities? Utilities need to understand this problem as is demands some real, on-the-ground leadership. Small and rural utilities are more costly to operate per thousand gallons than larger utilities. A 1997 study by the author showed that economy-of-scale manifested itself to a great extent with water and wastewater operations. The differences were not close – it is a lot less costly to operate large utilities vs small ones. Rural utilities complicate the issue further because not only is the number of customers limited, but the pipe per customer is less so the capital investment per customer is far higher than in urban areas. The impact is that utilities are under pressure to reduce rates to customers, or create a set of lower cost rates for those in poverty, while at the same time their costs are increasing and infrastructure demands are incrementally higher than their larger neighbors. The scenario cannot be sustained, especially when large portions of rural infrastructure was installed with FHA grants, meaning the customers never paid for the capital cost in the first place. There was no or lower debt, than what larger utility customers have. The rural rates since these investments have been set artificially lower than they should as a result. But with Congress talking about reducing SRF and FHA programs, FHA is unlikely to step in to replace their initial investment, meaning that the billions of rural investment dollars that will be needed in the coming years will need to be locally derived, and rate shock will become a major source of controversy in areas that are largely very conservative politically and tend to vote against projects that will increase costs to them.

The good news is that much of the rural infrastructure may be newer when compared to much of the urban infrastructure. So there is time to build the argument that local investment is needed. The community needs to be engaged in this discussion sooner as opposed to when problems occur. Saving for the infrastructure may be the best course since rural utilities will have limited access to the borrowing market because of their size, but that means raising rates now and keeping those saved funds as opposed to using them to deer rate increases. If ongoing efforts in the House deplete federal funding further, the pinch will be felt sooner by rural customers who will lose the federal dollars from SRF and FHA programs.

Figures 1 – Rural Counties

Figure 2. 100 lowest income Counties in the US

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_lowest-income_counties_in_the_United_States

Figure 3. Estimated population in poverty

http://www.raconline.org/racmaps/mapfiles/poverty.jpg

Figure 4. Where the Young People Are

http://www.raconline.org/maps/topic_details.php?topic=55

Figure 5. Where people are moving to http://www.raconline.org/maps

Figure 6 Unemployment 2008

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unemployment

Figure 7 Unemployment 2013 http://www.huduser.org/portal/pdredge/pdr_edge_featd_article_040