We have talked about reserves, the need for them, reasons why they are neglected and how to establish appropriate numbers (an area where more research is needed). Reserves are an issue when the economy tanks. We all recall the problem in 2008, but this is where utilities need to look beyond just their system to see what might be coming. 2008 was a problem that we should have seen coming, or at least planned for, but did not. But it means that we need to look at the national and local economic picture and understand a little about events beyond our reach that can affect us. Utilities and governments generally do not do this well.

In 2005-2007, it was very clear we had a property bubble going on. There was discussion on the news, financial channels, Wall Street Journal and even columns by economist like Paul Krugman. A few of us may have taken advantage of the bubble through prudent real estate sales, but many did not. Likewise, few utilities or governments planned for its inevitable fall. After the crunch hit, those who owed the least amount of money, had savings and had stable incomes fared better than those who did not. Same for governments. Unfortunately most Americans and most governments fell into the “did not” category.

So let’s look at a couple issues. First, we knew there was a bubble and should know that all bubbles pop. We had the tech stock bubble in the late 1990s. People on Wall Street knew that the investments had turned to real estate and bankers where busy loaning money out with no interest for two years, no money down, adjustable rate mortgages and the like. If you owned a computer you were inundated with Countryside and various other folks trying to loan you money. Or buy your house and pay you an annuity if you were older.

The reason that these “opportunities” were so prevalent was to help speculators who expected to own the property for short periods of time, or help those who might not have the means to buy time to get the means to support the payments. All the subsequent financial instruments discussed in books like “Too Big to Fail” come from tools used by bankers to disperse the risk associated with speculators and the risky. It made money for bankers and investment houses (remember they are private businesses beholden to their private stockholders).

Like all bubbles, we get caught up in the money being made by speculators (and yes if you invest in the stock market you are speculating). We try to grab onto the rising instruments to get ahead, but we forget that especially with real estate, the growth overall rate across the nation could only grow at the rate of population growth. It is basic supply and demand.

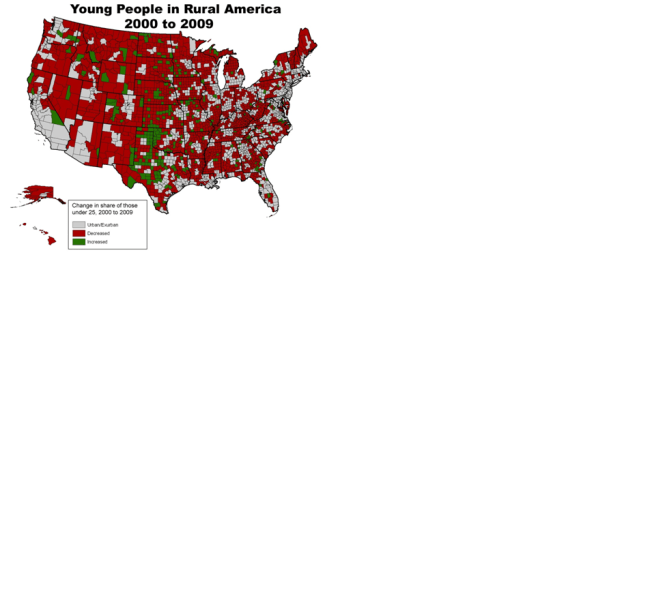

For governments, revenues rise, especially during real estate bubbles. Some bubbles last for years, which creates a distorted view of the future. In south Florida, there was a lot of buzz concerning water supply projections and arguments between regulatory staff and utilities over water supplies that were projected 20 years in the future, based on demand projections from 2000-2005. When the dust settled in 22011, most of those issued disappeared because virtually all projections were substantially revised downward. And most revenue growth projections were likewise revised downward and capacity needs delayed. Planning 20 years out is historically inaccurate because the global economy can impact local growth.

Of course these new projections are incorrect as well. Because the test period was 2005-2010 or 2000- 2010, the growth is stunted. So they are likely underestimating demand and revenues. Uncertainty with time means that the accuracy of projection decreases with time. As a result, simply relying on past projection methods increases risk that of significant deviations.

I do an exercise n class where I give students three sets of projections. 10 years apart, for 50 years. I tell them nothing else. The examples are The State of Nevada, Cleveland, and Collier County, FL. All are in the past (Cleveland is 1910-1950) There is absolutely no easy method that can project the growth in either Collier County or the State of Nevada, or that Cleveland’s population will drop in half. We could do the same with Detroit and never project that decrease either. But when you tell them where the population are and what year, the wheels start to turn. They realize that economics is a major issue. While Nevada and Collier grew from 1960-2000, the rate of change is likely to be very different in 2010 to 2020 due to the 2008 recession.

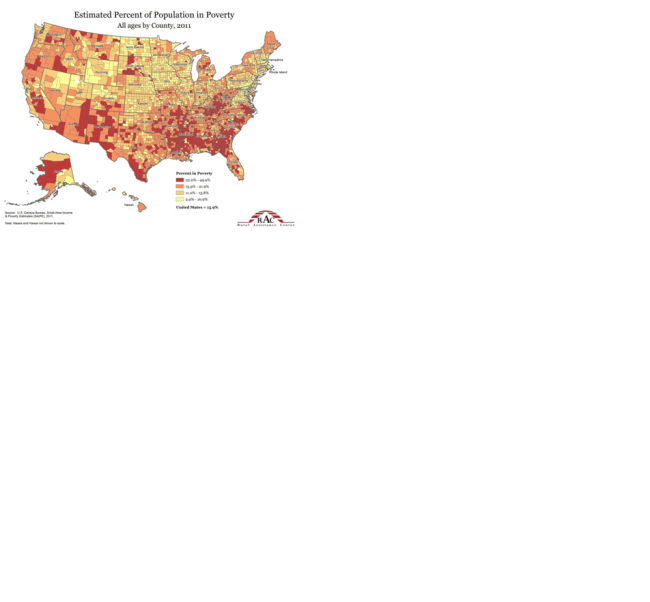

Tracking economic activity is a utility responsibility. We need to know what is really happening, and understand bubbles. We need to recognize that when property values and housing number increase fast, it will be short term. Plan for savings and reserves. Figure out what your recovery period might be. We need to understand our economic base. For example try this out and see what your conclusion is. Florida’s economy is based on three major industries: agriculture, tourism and housing. What could possibly go wrong with that model? Well if we have an economic problem nationally, 2 of 3 take major hits because people outside the state do not travel to Florida and retirements get put off. The economy gets hit hard and recovery is slow. We have experienced that exact phenomenon from 2009 to date. And many of those jobs are low wage positions which means the people who struggle most get hit hardest. Storm events can impact the state. Bit hits to all three, and agriculture is also a low wage industry. It is a precarious economic model that sets itself up for potential fluctuations. We need to plan for this. It is our responsibility, utility staff and decision-makers to plan and prepare for the next big event.