As water and sewer utilities, the public health and safety of our customers is our priority – it is both a legal and moral responsibility. The economic stability and growth of our community depends on reliable services or high quality. The priority is not the same with private business. Private businesses have a fiduciary responsibility to their stockholders, so cutting services will always be preferred to cutting profits. Therein lies the difference and yet the approach is different. Many corporations retain reserves for stability and investment and to protect profits. Many governments retain inadequate reserves which compromises their ability to be stable and protect the public health and safety. Unlike corporations, for government and utilities, expenses are more difficult to change without impacting services that someone is using or expects to use or endangering public health. Our recent economic backdrop indicates that we cannot assume income will increase so we need to reconsider options in dealing with income (revenue) fluctuations. If there are no reserves, when times are lean or economic disruptions occur (and they do regularly), finding funds to make up the difference is a problem. The credit market for governments is not nearly as “easy” to access as it is for people in part because the exposure is much greater. If they can borrow, the rates may be high, meaning greater costs to repay. Reserves are one option, but reserves are a one-time expense and cannot be repeated indefinitely. So if your reserves are not very large, the subsequent years require either raising taxes/rates or cutting costs. An example of the problem is illustrated in Figure 1. In this example the revenues took a big hit in 2009 as a result of the downturn in the economy. Note it has yet to fully return to prior levels as in many utilities. This system had accumulated $5.2 million in reserves form 2000-2008, but has a $5.5 million deficit there after. Reserves only go so far. Eventually the revenues will need to be raised, but the rate shock is far less if you have prudently planned with reserves. You don’t get elected raising rates, but you have a moral responsibility to do so to insure system stability and protection of the public health. So home much is enough for healthy reserves? That is a far more difficult question. In the past 1.5 months of operating reserves was a minimum, and 3 or more months was more common. However, the 2008-2011 economic times should change the model significantly. Many local governments and utilities saw significant revenue drops. Property tax decreases of 50% were not uncommon. It might take 5 to 10 years for those property values to rebound so a ten year need might be required. Sales taxes dropped 30 percent, but those typically bounce back more quickly - 3-5 years. Water and sewer utilities saw decreases of 10-30%, or perhaps more in some tourist destinations. Those revenues may take 3-5 years to rebound as well. Moving money from the utility to the general fund, hampers the situation further. Analysis of the situation, while utility (government) specific, indicates that appropriate reserves to help weather the economic downturns could be years as opposed to months. The conclusion is that governments and utilities should follow the model of trying to stabilize their expenses. Collect reserves. Use them in lean times. Develop a tool to determine the appropriate amounts. Educate local decision-makers and the public. Develop a financial plan that accounts for uncertainty and extreme events that might impact their long-term stability. Take advantage of opportunities and most of all be ready for next time. In other words, plan for that rainy day.

utilities

SEA LEVEL RISE AND FLOOD PROTECTION

Regardless of the causes, southeast Florida, with a population of 5.6 million (one-third of the State’s population), is among the most vulnerable areas in the world for climate change due its coastal proximity and low elevation (OECD, 2008; Murley et al. 2008), so assessing sea level rise (SLR) scenarios is needed to accurately project vulnerable infrastructure (Heimlich and Bloetscher, 2011). Sea level has been rising for over 100 years in Florida (Bloetscher, 2010, 2011; IPCC, 2007). Various studies (Bindoff et al., 2007; Domingues et al., 2008; Edwards, 2007; Gregory, 2008; Vermeer and Rahmstorf, 2009; Jevrejeva, Moore and Grinsted, 2010; Heimlich, et al. 2009) indicate large uncertainty in projections of sea level rise by 2100. Gregory et al. (2012) note the last two decades, the global rate of SLR has been larger than the 20th-century time-mean, and Church et al. (2011) suggested further that the cause was increased rates of thermal expansion, glacier mass loss, and ice discharge from both ice-sheets. Gregory et al. (2012) suggested that there may also be increasing contributions to global SLR from the effects of groundwater depletion, reservoir impoundment and loss of storage capacity in surface waters due to siltation.

Why is this relevant? The City of Fort Lauderdale reported last week that $1 billion will need to be spent to deal with the effect of sea level rise in Fort Lauderdale alone. Fort Lauderdale is a coastal city with canals and ocean property, but it is not so different from much of Miami-Dade County, Hollywood, Hallandale Beach, Dania Beach and host of other coastal cities in southeast Florida. Their costs may be a harbinger of costs to these other communities. Doing a “back of the napkin” projection of Fort Lauderdale’s cost for 200,000 people to the additional million people in similar proximity to Fort Lauderdale means that $5 billion could easily be spent over the next 100 years for costal impoundments like flap gates, pumping stations, recharge wells, storm water preserves, exfiltration trenches and as discussed in this blog before, infiltration galleries. Keep in mind that would be the coastal number and we often ignore ancillary issues. At the same time, an addition $5 to 10 billion may be needed for inland flooding problems due to the rise of groundwater as a result of SLR.

The question raised in conjunction with the announcement was “is it worth it?” I suggest the answer is yes, and not just because local politicians may be willing to spend money to protect their constituents. The reality is that $178 billion of the $750 billion economy of Florida, and a quarter of its population, is in the southeast. With nearly $4 trillion property values, raising a few billion for coastal improvements over 100 years is not an insurmountable task. It is billions in local engineering and construction jobs, while only impacting taxpayers to the tune of less than 1/10 of a mill per year on property taxes. This is still not an insurmountable problem.

I think with good leadership, we can see our way. However, that leadership will need to overcome a host of potential local community conflicts as some communities will “get more” than others, yet everyone benefits across the region. New approaches to working together will need to be tried. But the problem is not insurmountable, for now…

INVESTING IN INFRASTRUCTURE

When we ask what the biggest issues facing water and sewer are in the next 20 years, the number one answer is usually getting a handle on failing infrastructure. Related to infrastructure is sustainability of supplies and revenue needs. Resolving the infrastructure problem will require money, which means revenues, and overcoming the resistance to fully fund water and sewer system by local officials, the potential for significant costs or shortfalls for small, rural systems and the increasing concern about economically disadvantaged people.

The US built fantastic infrastructure systems in the mid-20th century that allowed our economy to grow and for us to be productive. But like all tools and equipment, it degrades, or wears out with time. Our economy and our way of life requires access to high quality water and waste water. So this will continue to be critical.

ASCE and USEPA have both noted the deteriorated condition of the water and wastewater systems. In the US, we used to spend 4% of the gross GNP on infrastructure. Currently is it 2%. Based on the needs and spending, there is a clear need to reconstruct system to maintain our way of life. This decrease in funding comes at a time when ASCE rates water and wastewater system condition as a D+ and estimates over $3 trillion in infrastructure investment will be needed by 2020. USEPA believes infrastructure funding for water and sewer should be increased by over $500 billion per year versus the proposed federal decrease of similar amounts or more.

Keep in mind much of what has made the US a major economic force in the middle 20th century is the same infrastructure we are using today. Clearly there is research to indicate there is greater need to invest in infrastructure while the politicians move the other way. The public, caught in the middle, hears the two sides and prefers less to pay on their bills, so sides with the politicians as opposed to the data. Make no mistake, our way of life results from extensive, highly efficient and economic infrastructure systems.

In many ways we are victims of our own success. The systems have run so well, the public takes them for granted. It is hard to make the public understand that our cities are sitting on crumbling systems that have suffered from lack of adequate funding to consistently maintain and upgrade. Public agencies are almost always reactive, as opposed to pro-active, which is why we continuously end up in defensive positions and at the lower end of the spending priorities. So we keep deferring needed maintenance. The life cycle analysis concepts used in business would help. A 20 year old truck, pump, backhoe, etc. just aren’t cost effective to operate and maintain.

Another part this problem is that people have grown used to the fact that water is abundant, cheap, and safe. Open the tap and here it comes; flush the toilet and there it goes, without a thought as to what is involved to produce, treat and distribute potable water as well as to collect, treat, and discharge wastewater.

Water and Sewer utilities are being funded at less than half the level needed to meet the 30 year demands. Meanwhile relying on the federal government, which is trying to reduce funding for infrastructure for local utilities is not a good plan either. We need education, research and demonstrations to show those that control funding of the needs. The education many be the toughest part because making the those that control funding agree to increase rates carries a potential risk to them personally. But there are no statues to those that don’t raise rates – only those with vision. We need to instill vision in our decision-makers.

Students Get Jobs, and Bring a Fresh Perspective

We get to start the new semester this week. The economy is looking up in Florida. Unemployment is down, although the job growth appears to be mostly minimum wage jobs. So it is useful to look at last semester’s graduates and see how they are doing. The good news is they are getting jobs. In fact our seniors mostly have jobs or internships and none of them are minimum wage jobs. Excellent news, but let’s look at the new graduates and the workplace.

A lot of our assumptions about the workplace will change in the 21st century. The workplace at the “office” is less necessary and younger workers are more comfortable working outside the office environment. They may be more productive than 20th century managers think they will be because of the side benefits that flex hours allow. Their entry into the workforce places four generations at work at once: Traditionalists, Baby Boomers, Gen X, and Gen Y or Millennials. The latter are the fastest growing segment of the workforce, and are already a larger percent of the workforce than Gen X or Traditionists. The Traditionalists are retiring and are expected to be under 8 % in 2015. Gen X and Gen Y will encompass about a third of the workforce going forward.

All of these groups have different perspectives. Recent studies indicate the following. Baby Boomers grew up post-WWII in a time of change and reform. Some believe they are instruments of change. They are optimistic, hard-working and motivated by position. Gen X grew up in an era of both parents working, so are resourceful and hardworking, but not as motivated by position. They are independent, and prefer to work on their own. And many are contributing to the way government operates throughout the world. They accept technology as a way to involve others. The use of online means to solicit feedback in government is particularly a Gen X phenomenon. Public participation, traditionally are arena where limited public involvement actually occurs except with highly unpopular issues.

Gen Y was born in an era when both parents worked, but in their off-time, the parents spent more focus on the kids. Think of no winners or losers in sports, but at the same time they have had unprecedented access to technology and are often well ahead of their work mates with respect to the use of tools in the workplace. But, they are resourceful and can easily overcome technology barriers in the workplace. They care about their image and the world around them. We can use that to implement change.

However, Gen Y is facing a workplace that clearly has winners as well as some skepticism about technology. While we can expect some difficulties, it is up to the Gen X and Baby Boomers to help Gen Y make the transition. They have fresh viewpoints as they have had to be creative to get ahead. Just doing things “the same old way,” doesn’t cut it. I actually find this refreshing and a positive challenge to me because I use these challenges to go back of evaluate what my thinking was (or is). We need to embrace this perspective and channel their energy and independence to solving today’s problems.

We need to help them acclimate to the business world, while understanding that their motivations are not the same as Dan Pink notes in his book “Drive.” We need new ideas and perspectives while welcoming them to the workplace. That is how we improve productivity, product new ways to work, and develop new tools. We need all of these in the utility industry as we need better ways to upgrade infrastructure and deliver our services.

There is a lot of talk about the difficulties that Gen Y is having getting jobs. They often lack experience, but how do you get experience if no one hires you. It is circular logic and we have all been there.

We need to give the kids a chance. I see a lot of potential in our graduates, nearly all of whom are Gen Y. I see many who are hard working and know how to find answers to their questions. They are far better prepared than many think. We get comments all the time about how good our students are. That is good, because the truth is, especially in the engineering and utility world, the Gen Y workforce does not understand why things were done a certain way in the past, nor why they should remain that way. I actually find this refreshing and a positive challenge to me because I use these challenges to go back of evaluate what my thinking was (or is). We need to embrace this perspective and channel their energy and independence to solving today’s problems. They offer fresh ideas – and don’t necessary understand why. That’s ok. Long-term engineering graduates will make contributions to our water, sewer and other infrastructure.

Rural Utilities Part 2

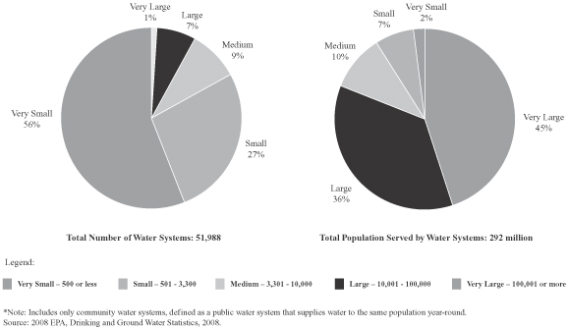

In the last blog I talked about the challenge to rural utilities, many of which serve relatively few people and have used federal monies to pay for a lot of their infrastructure. In this blog we will take a look at the trends for community water systems which are defined as systems that serve at least 15 service connections or serve an average of at least 25 people for at least 60 days a year. EPA breaks the size of systems down as follows:

- Very Small water systems serve 25-500 people

- Small water systems serve 501-3,300 people

- Medium water systems serve 3,301-10,000 people

- Large water systems serve 10,001-100,000 people

- Very Large water systems serve 100,001+ people

Now let’s take a look at the breakdown (from NRC 1997). In 1960, there were about 19,000 community water utilities in the US according to a National Research Council report published in 1997. 80% of the US population was served. in 1963 there were approximately 16,700 water systems serving communities with populations of fewer than 10,000; by 1993 this number had more than tripled—to 54,200 such systems. Approximately 1,000 new small community water systems are formed each year (EPA, 1995). In 2007 there were over 52,000 community water systems according to EPA, and by 2010 the number was 54,000. 85% of the population is served. So the growth is in those small systems with incidental increases in the total number of people served (although the full numbers are more significant).

TABLE 1 – U.S. Community Water Systems: Size Distribution and Population Served

|

|

Number of Community Systems Serving This Size Community a |

Total Number of U.S. Residents Served by Systems This Size b> |

||

|

Population Served |

1963 |

1993 |

1963 |

1993 |

|

Under 500 |

5,433 (28%) |

35,598 (62%) |

1,725,000 (1%) |

5,534,000 (2%) |

|

501-10,000 |

11,308 (59%) |

18,573 (32%) |

27,322,000 (18%) |

44,579,000 (19%) |

|

More than 10,000 |

2,495 (13%) |

3,390 (6%) |

121,555,000 (81%) |

192,566,000 (79%) |

|

Total |

19,236 |

57,561 |

150,602,000 |

242,679,000 |

|

a Percentage indicates the fraction of total U.S. community water supply systems in this category. b Percentage is relative to the total population served by community water systems, which is less than the size of the U.S. population as a whole. SOURCES: EPA, 1994; Public Health Service, 1965. |

||||

Updating these numbers, there are over 54,000 systems in the US, and growth is almost exclusively in the very small sector. 93% are considered to be small or very small systems—serving fewer than 10,000 people. Even though these small systems are numerous, they serve only a small fraction of the population. Very small systems, those that serve 3,300 people or fewer make up 84 percent of systems, yet serve 10 percent of the population. Most critical is the 30,000 new very small systems that serve only 5 million people (averaging 170 per system). In contrast, the very large systems currently serve 45% of the population. Large plus very large make it 80%. The 800 largest systems (1.6%) serve more than 56 percent of the population. 900 new systems were added, but large systems served an additional 90 million people.

What this information suggests if that the large and very large sector has the ability to raise funds to deal with infrastructure needs (as they have historically), but that there may be a significant issue for smaller, rural system that have grown up with federal funds over the past 50 years. As these system start to come to the end of their useful life, rural customers are in for a significant rate shock. Pipeline average $100 per foot to install. In and urban area with say, 60 ft lots, that is $3000/household. In rural communities, the residents may be far more spread out. As an example, a system I am familiar with in the Carolinas, a two mile loop served 100 houses. That is a $1.05 million pipeline for 100 hours or $10,500 per house. With dwindling federal funds, rural customers, who are already making 20% less than their urban counterparts, and who are used to very low rates, that generally do not account for replacement funding, will find major sticker shock.

This large number of relatively small utilities may not have the operating expertise, financial and technological capability or economies of scale to provide services or raise capital to upgrade or maintain their infrastructure. Keep in mind that small systems have less resources and less available expertise. In contrast the record of large and very large utilities, EPA reports that 3.5 percent of all U.S. community water systems violated Safe Drinking Water Act microbiological standards one or more times between October 1992 and January 1995, and 1.3 percent violated chemical standards, according to data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)..

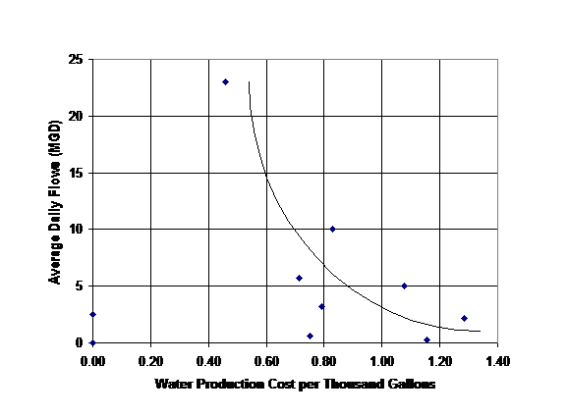

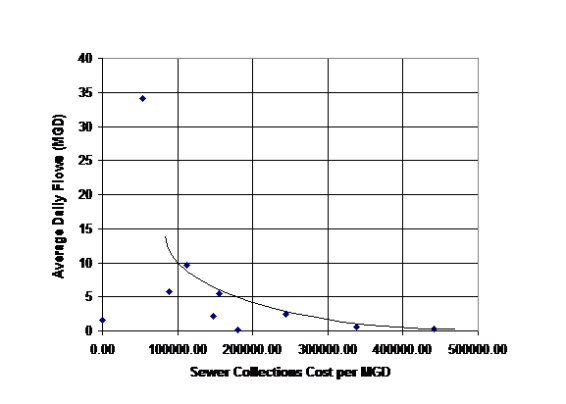

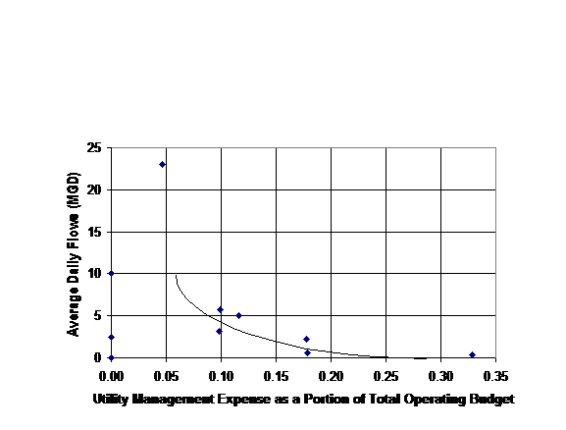

EPA and professionals have long argued that centralized infrastructure for water and sewer utilities makes sense form an economy of scale perspective. Centralized drinking water supply infrastructure in the United States consists dams, wells, treatment plants, reservoirs, tanks, pumps and 2 million miles of pipe and appurtenances. In total this infrastructure asset value is in the multi-trillion dollar range. Likewise centralized sanitation infrastructure in the U.S. consists of 1.2 million miles of sewers and 22 million manholes, along with pump stations, treatment plants and disposal solutions in 16,024 systems. It is difficult to build small reservoirs, dams, and treatment plants as they each cast far more per gallon to construct than larger systems. Likewise operations, despite the allowance to have less on-site supervision, is far less per thousand gallons for large utilities when compared to small ones. The following data shows that the economy-of-scale argument is true:

- For water treatment, water distribution, sewer collection and wastewater treatment, the graphics clearly demonstrated the economy-of-scale of the larger utility operations versus small scale operations (see Figures 2-5).

- The administrative costs as a percentage of the.total budget parameter also demonstrated the economy-of-scale argument that larger utilities can perform tasks at a lesser cost per unit than the smaller utilities (see Figure 6).

Having reviewed the operations costs, the next step was to review the existing rates. Given the economy-of-scale apparent in Figures 2 to 6, it was expected that there would be a tendency for smaller system to have higher rates. Figures 2-6 demonstrate this phenomena.

So what to do? This is the challenge. Rate hikes are the first issue, a tough sell in areas generally opposed to increases in taxes, rates and charges and who use voting to impose their desires. Consolidation is anothe5r answer, but this is on contrast to the independent nature of many rural communities. Onslow County, NC figured out this was the only way to serve people efficiently 10 years ago, but it is a rougher sell in many, more rural communities. Infrastructure banks might help, the question is who will create them and will the small system be able to afford to access them. Commercial financing will be difficult because there is simply not enough income to offset the risk. The key is to start planning now for the coming issue and realize that water is more valuable than your iPhone, internet, and cable tv. In most cases we pay more for each of them than water (see Figure 7). There is something wrong with that…

Figure 1 Breakdown of Size of Systems

Fig 2 Cost of Water Treatment

Fig 3 Cost of Water Distribution

Fig 4 Cost of Sewer Collection

Fig 5 Cost of Sewer Treatment

Fig 6 Cost of Administration as a percent of total budget

FIgure 7 Water vs other utilities

Power to the Utilities?

Local utilities are among the largest power users in their communities. This is why power companies make agreements with utilities at reduced cost if the utilities will install backup power supplies. The peak power generation capacity as well as backup capacity is at the local utilities and other large users. Power companies can delegate this capital cost to large users without the investment concerns. It works for both parties. In addition, power companies spend effort to be more efficient with current power supplies, because recovering the costs for new, large plants is difficult, and in ways, cost prohibitive. Hence small increment options are attractive, especially when they are within high demand areas (distributed power). The use of localized wind, solar and on-site energy options like biogas are cost effective investments if sites can be found. That is where the utilities come in. Many utilities have sites. Large water utilities may have large reservoirs and tank sites that might be conducive to wind or solar arrays. Wind potential exists where there are thermal gradients or topography like mountains. Plant sites with many buildings and impervious areas could also be candidates for solar arrays and mini-wind turbines. Wastewater plants are gold mines for digester gas that is usually of high enough quantity to drive turbines directly. So utilities offer potential to increase distributed power supplies, but many water/wastewater utilities lack the expertise to develop and maintain these new options, and the greatest benefit is really to power companies that may be willing to provide as much money in “rent” to the utilities as they can save. Power entities obviously have the expertise and embedded experience to run distributed options optimally. So why don’t we do this?

I would speculate several reasons. First, the water/wastewater utilities have not really considered the option, and if they do there is the fear of having other folks on secure treatment sites. That can be overcome. The power entities have not really looked at this either. The focus in the power industry is to move from oil-based fuels to natural gas to accumulate carbon credit futures, the potential for lower operating costs and better efficiency of current facilities to reduce the need for capital investments. Power entities operate in a tight margin just like water/wastewater utilities do so saving where you can is a benefit. There are limited dollars to invest on both sectors and political and/or public service commission issues to overcome to invest in distributed power options at water/wastewater facilities.

But a longer-term view is needed. While fossil fuels have worked for us for the last 100 years, the supply is finite. We are finding that all that fracking might not give us 200 years, but more like 20-40 years of fuel. We have not solved the vehicle fuel issue and fossil fuels appear to be the best solution for vehicles for the foreseeable future which means they will compete directly with power demands. Natural gas can be used for vehicles fairly easily as evidenced by the many transit and local government fleets that have already converted to CNG.

The long-term future demands a more sustainable green power solution. We can get to full renewable power in the next 100 years, but the low hanging fruit need to be implemented early on so that the optimization of the equipment and figuring out the variables that impact efficiency can be better understood than they are now. For example, Leadville, CO has a solar array, but the foot of snow that was on it last September didn’t allow it to work very well. And solar arrays do use water to clean the panels. Dirty panels are nowhere near as efficient as clean ones. We need to understand these variables.

Area that are self sufficient with respect to power will benefit as the 21st century moves forward. There are opportunities that have largely been ignored with respect to renewable power at water and wastewater facilities, and with wastewater plants there is a renewable fuel that is created constantly. Wastewater plants are also perfect places to receive sludge, grease, septage, etc which increase the gas productions. There are examples of this concept at work, but so far the effort is generally led by the wastewater utilities. An example is East Bay Municipal Utility District (Oakland, CA) which produces 120% of its power needs at its wastewater plant, so sells the excess power back to the power company. There are many large wastewater plants that use digester gas to create power on-site to heat digesters or operate equipment. Others burn sludge in on-site incinerators to produce power. But so far the utilities are only reducing their cost as opposed to increasing total renewable power supplies. A project is needed to understand the dynamics further. If you are interested, email me as I have several parties wishing to participate in such a venture.

SRF Wars in Congress – What it Means to Utilities

As 2014 is only a month away, expect water and sewer infrastructure to become a major issue in Congress. While Congress has failed to pass budgets on-time for many years, already there are discussions about the fate of federal share of SRF funds. The President has recommended reduction in SRF funds of $472 million, although there is discussion of an infrastructure fund, while the House has recommended a 70% cut to the SRF program. Clearly the House sees infrastructure funding as either unimportant (unlikely) or a local issue (more likely). Past budgets have allocated over $1.4 billion, while the states put up a 20% match to the federal share. A large cut in federal funds will reverberate through to local utilities, because many small and medium size utilities depend on SRF programs because they lack access to the bond market. In addition, a delay in the budget passage due to Congressional wrangling affects the timing of SRF funds for states and utilities, potentially delaying infrastructure investments.

This decrease in funding comes at a time when ASCE rates water and wastewater system condition as a D+ and estimates over $3 trillion in infrastructure investment will be needed by 2020. USEPA notes that the condition of water and wastewater systems have reached a rehabilitation and replacement stage and that infrastructure funding for water and sewer should be increased by over $500 billion per year versus a decrease of similar amounts or more. Case Equipment and author Dan McNichol have created a program titled “Dire Straits: the Drive to Revive America’s Ailing Infrastructure” to educate local officials and the public about the issue with deteriorating infrastructure. Keep in mind much of what has made the US a major economic force in the middle 20th century is the same infrastructure we are using today. Clearly there is technical momentum to indicate there is greater need to invest in infrastructure while the politicians move the other way. The public, caught in the middle, hears the two sides and prefers less to pay on their bills, so sides with the politicians as opposed to the data.

Local utilities need to join the fray as their ability to continue to provide high quality service. We need to educate our customers on the condition of infrastructure serving them. For example, the water main in front of my house is a 50 year old asbestos concrete pipe that has broken twice in the past 18 months. The neighborhood has suffered 5 of these breaks in the past 2 months, and the City Commission has delayed replacement of these lines for the last three years fearing reprisals from the public. Oh and the road in front of my house is caving in next to where the leak was. But little “marketing” by the City has occurred to show the public the problem. It is no surprise then that the public does not recognize the concern until service is interrupted. So far no plans to reinitiate the replacement in front of my house. The Commission is too worried about rates.

Water and sewer utilities have been run like a business in most local governments for years They are set up as enterprise funds and people pay for what they use. Just like the private sector. Where the process breaks down is when the price is limited while needs and expenses rise. Utilities are relatively fixed in their operating costs and I have yet to find a utility with a host of excess: workers. They simply do not operate in this manner. Utilities need to engage the public in the infrastructure condition discourse, show them the problems, identify the funding needs, and gain public support to operate as any enterprise would – cover your costs and insure you keep the equipment (and pipes) maintained, replacing them when they are worn out. Public health and our local economies depend on our service. Keep in mind this may become critical quickly given the House commentary. For years the federal and state governments have suggested future funding may not be forthcoming at some point and that all infrastructure funding should be local. That will be a major increase in local budgets, so if we are to raise the funds, we need to solicit ratepayer support. Now!

Why Build Green?

In the field of engineering, the concept of sustainability refers to designing and managing to fully contribute to the objectives of society, now and in the future, while maintaining the ecological, environmental, and economic integrity of the system. Most people would agree that structures such as buildings that have a lifespan measured in decades to centuries would have an important impact on sustainability, and as such, these buildings must be looked at as opportunities for building sustainably. When people think about green buildings, what generally comes to mind is solar panels, high efficiency lighting, green roofs, high performance windows, rainwater harvesting, and reduced water use. This is true, but building green can be so much more.

The truth is that the built environment provides countless benefits to society; but it has a considerable impact on the natural environment and human health (EPA 2010). U.S. buildings are responsible for more carbon dioxide emissions annually than those of any other countries except China (USGBC 2011). In 2004, the total emissions from residential and commercial buildings were 2,236 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2), more than any other sector including the transportation and industrial sectors (USGBC 2011). Buildings represent 38.9% of U.S. primary energy use,72% of U.S electricity consumption (and 10% worldwide), 13.6% of all potable water, and 38% of all CO2 emissions (USGBC 2011). Most of these emissions come from the combustion of fossil fuels to provide heating, cooling, lighting, and to power appliances and electrical equipment (USGBC 2011). Since buildings have a lifespan of 50 to 100 years during which they continually consume energy and produce carbon dioxide emissions, if half of the new commercial buildings were built to use only 50 percent less energy, it would save over 6 million metric tons of CO2 annually for the life of the buildings. This is the equivalent of taking more than one million cars off the roads each year (USGBC 2011).

The United States Green Building Council (USGBC) expects that the overall green building market (both non-residential and residential) to exceed $100 billion by 2015 (McGraw Hill Construction 2009). Despite the economic issues post 2008, it is expected that green building will support 7.9 million U.S. jobs and pump over $100 million/year into the American economy (Booz Allen Hamilton, 2009). Local and state governments have taken the lead with respect to green building, although the commercial sector is growing.

Green building or high performance building is the practice of creating structures using processes that are environmentally responsible and resource efficient throughout a building’s life cycle, from site to design, construction, operation, maintenance, renovation, and deconstruction (EPA 2010). High performance building standards expand and complement the conventional building designs to include factors related to: economy, utility, durability, sustainability, and comfort. At the same time, green building practices are designed to reduce the overall impact of the built environment on human health and use natural resources more responsibly by more efficiently using energy, water, and other resources, while protecting occupant health and improving employee productivity.

High Performance Buildings are defined by incorporating all major high performance attributes such as energy efficiency, durability, life-cycle performance, natural lighting, and occupant productivity (EPA 2010). High performance buildings are constructed from green building materials and reduce the carbon footprint that the building leaves on the environment. A LEED-certified green building uses 32% less electricity and saves around 30% of water use annually (USGBC 2011). Building owners know that there is a return on investment of up to 40% by constructing a green building as a result of savings to energy and water (NAU 2012).

The cost per square foot for buildings seeking LEED Certification falls into the existing range of costs for buildings not seeking LEED Certification (Langdon, 2007). An upfront investment of 2% in green building design, on average, results in life cycle savings of 20% of the total construction costs – more than ten times the initial investment (Kats, 2003), while building sale prices for energy efficient buildings are as much as 10% higher per square foot than conventional buildings (Miller et al., 2007). At the same time, the most difficult barrier to green building that must be overcome includes real estate and construction professionals who still overestimate the costs of building green (World Business Council, 2008).

New data indicates that the initial construction cost of LEED Certified buildings can sometimes cost no more than traditional building practices. A case study done by the USGBC showed that the average premium for a LEED certified silver building was around 1.9% per square foot more than a conventional building. The premium for gold is 2.2% and 6.8% for platinum. These numbers are averaged from all LEED-registered projects, so the data is limited, but demonstrates that in some cases it does not cost much extra to deliver a LEED certified project which greatly improves the value of the building and lowers operating costs (Kuban 2010). The authors’ experience with the Dania Beach nanofiltration plant indicated the premium was under 3% to achieve LEED-Gold certification compared to standard construction.

So the question is, why don’t we see more green buildings? We know water plants can be green (Dania Beach Nanofiltration Plant), but that was the first nanofiltration plant in the world to be certified Gold. The SRF programs prioritize green infrastructure – so why do more people not pursue them? It may be an education process. Or maybe the market just has not caught up. CIties and states are leading the way here. Utilities may want to look at this as well.

Engineers are getting hired!

Graduation is two weeks away for students in the Fall semester. The good news is that unemployment is down which means more students may find jobs. We see my students, civil engineers, nearly fully employed for the second straight semester. That is a good sign that economy is bouncing back.

Many are being hired by utilities and contractors. The utilities are starting to spend money after several years of lean revenues. Unfortunately many of these utilities were lean because their local governments have increased general fund contributions to reduce tax burdens of residents. Reducing tax burdens by moving more money from utilities to general funds hits the utility twice – infrastructure improvements get delayed and catchup on deferred maintenance mean the hit is double the pay as you go policy. It is no surprise that our infrastructure condition continues to deteriorate when funds are diverted for other purposes. Hopefully the trend will reverse, but I am not optimistic.

Contractor hiring is more interesting. It seems that contractors are having many of the same issues as utilities have talked about for a number of years: an aging workforce in the upper levels of the organization. However the contractors are seeing that young engineers have a skill set not currently existing in many contractor organizations. Contracting in lean times is a limited profit margin business. Competing for low bid contracts further limits profits. However when 40% of the cost for construction is often associated with materials, and 20-25% of materials may be wasted, finding a way to be more efficient can save a lot of money. Engineers know software and some schools, like FAU, have their students use 3 dimensional (3D) BIM software for their design projects. The BIM software allows contractors to merge drawings into 3 dimensions, finding conflicts, solving them early and identifying means to reduce materials. For example, many pieces could be cut out of gypsum board, but often only one is cut. The rest is tossed. Saving big on materials creates added profits at the same price. The benefit is seen as being well worth the cost to contractors. As more contractors move this direction, more engineers will the hired; a good trend.

The engineering profession should benefit from this change. As contractors hire engineers, there is the potential for better communication between engineers on contractor teams and design engineers. The only question is getting the engineering community to adopt the same kind of attitude toward the new software tools like 3D software. At present, far too many engineers do not believe the risks are reduced sufficiently by the costs of the software. But adopting new methods for design will help communication with contractors and other engineers. That communication has a benefit in saving dollars and limiting the potential for claims against design firms when conflicts are found in the design drawings. We find that establishing a partnering mentality on projects fosters a better working relationship. Great things can be accomplished.