Over Labor Day I took my wife to Las Vegas for her birthday to see the Cirque du Soliel show “O”, the Hoover dam and experience Vegas. She’d never been before. And it is a milestone birthday. We had a nice trip. The “O” show is all it is said to be. Another spectacular event! The hoover dam is an amazing 80 year old structure, designed to hold water for Arizona, California and Nevada, as well as make some power. Of course all three have long outgrown the reservoir. And the level drops each year to where it is 300 feet below its height less than 15 years back. A colossal feat of engineering that led to huge development in the arid west. The nearby Boulder City was created to build the dam. Las Vegas would not exist without its water. Water in the desert! The Anasazi’s would be amazed.

Tag Archives: drought

Is this a good idea?

In the vein of more growth is always better mentality, the following struck me as I was in Colorado last month. Front Range politics are a big deal in Colorado because virtually all the people in the state live within 60 miles of Denver. The following table outlines the populations of the Front Range counties and their growth trends over the past three years. Big growth. So the local politicians are happy. Growth is good.

| The Front Range Urban Corridor | |||

| County | 2012 Estimate | 2010 Census | Change |

| Larimer County | 310,487 | 299,630 | +3.62% |

| Weld County | 263,691 | 252,825 | +4.30% |

| Boulder County | 305,318 | 294,567 | +3.65% |

| City and County of Denver | 634,265 | 600,158 | +5.68% |

| Arapahoe County | 595,546 | 572,003 | +4.12% |

| Jefferson County | 545,358 | 534,543 | +2.02% |

| Adams County | 459,598 | 441,603 | +4.07% |

| Douglas County | 298,215 | 285,465 | +4.47% |

| City and County of Broomfield | 58,298 | 55,889 | +4.31% |

| Elbert County | 23,383 | 23,086 | +1.29% |

| Park County | 16,029 | 16,206 | −1.09% |

| Clear Creek County | 9,026 | 9,088 | −0.68% |

| Gilpin County | 5,491 | 5,441 | +0.92% |

| El Paso County | 644,964 | 622,263 | +3.65% |

| Teller County | 23,389 | 23,350 | +0.17% |

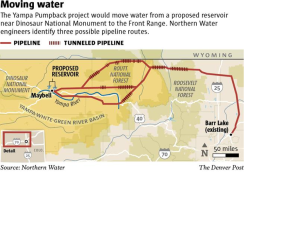

Then I read an article by Bruce Finley of the The Denver Post entitled “Colorado shies from big fix as proliferating people seek more water.’ The concept is to continue the state’s tradition of moving water from the wetter west side of the Rockies to the drier east side. The current fix is to build a huge reservoir by Dinosaur National Monument (in the middle of the west Colorado desert), then divert 97 billion gallons a year from the Yampa River through a 250-mile pipeline across the Continental Divide to the Front Range to defray Colorado’s projected 2050 water shortfall of 163 billion gallons. The Yampa Pumpback would be the 31st cross divide diversion Colorado has built since the 1930s.

Now the plan has hit a snag, whereby the EIS for the project indicates to meet needs, it would be the Front Range that bears the risks of not enough water in dry years as a part of negotiations for water entitlements under the interstate treaty that divvies the Colorado River. Once that is resolved, the project would cost billions and take years to construct. Ok, the Front Range is water limited. And we all know it. The problem is people like Northern Water manager Eric Wilkinson who the article quotes as saying. “With the number of people coming here, we’re going to have to look at all alternatives. Conservation isn’t the silver bullet; it’s also going to take additional infrastructure…. These people need water, and they’re willing to pay for that water.” In other words, we need more growth! So in the meantime, development competes with agriculture or replaces agriculture on the semi-arid high plains. The article suggests that cities and industries seeking more water would absorb hundreds of thousands of acres of agricultural land water rights if unable to divert more across mountains, something the governor is a little concerned about. They would just buy them out. So less agriculture when we probably will need that land later.

So in that vein, I noted the following at the airport. One is a nice field of grain. Golden in the summer sun. Across the street, the golden field is being converted to 300 houses. You can see the pipe and the equipment. And my question is – Is this really a good idea?

More Direct Potable Reuse?

This month’s Journal for AWWA has several articles devoted to direct potable reuse (DPR). Total Water Solutions is the moniker that AWWA has tapped lately as the organization has moved to the message that water sources cannot be separated. California believes that 40% of its urban water use can be recycled to direct potable reuse, which can address a lot of the drought concerns for urban users (11% of California’s water use). The technology is available to make DPR a reality. The concerns involve insuring system reliability (i.e. redundancy in processes), and public perception of DPR. As I noted in a prior blog, there are two cities in Texas already doing DPR. There are several places in California doing indirect potable reuse (IPR) which basically involves injected the water into an aquifer or releasing it in an upstream reservoir. The treatment is basically the same for both but the separation is creates a different public opinion. One that is not so different than discharging wastewater to rivers that serve as water supplies downstream. Both IPR and DPR were unheard of as ideas outside southern California until more recently. But in the past several years, both have seen a significant change in Texas, California and Florida. Water-logged south Florida has looked at 5 IPR projects in the past 7 years, and has a couple reuse ASR systems. Should drought conditions return, these projects may not be so far-out (note we are at 25% normal rainfall in southeast Florida – but water use is 10% below 2005 levels).

Ethics and Sustainability

There is an interesting ethical issues that arises in this discussion also. Engineers are entrusted to protect the public health, safety and welfare. When there were few people, projects did not impact many so little thought was given to the “what could possible happen” question. We are still paying for that. When bad things happen, the precedent has unfortunately been set that somehow “the government” will resolve this. An old 1950s BOR director said he thought he was “a hero because he helped create more room for people” in the west with dams and water projects. He did accomplish that, except that while there were more people coming, the resources were never analyzed for sustainability, nor the impact it might have on the existing or potential future economic resources. But once the well runs dry, I think we just assumed that another solution would resolve any issue. But what is if doesn’t?

There are many water supply examples, where we have engineered solutions that have brought water or treated water to allow development. South Florida is a great example – we drained half a state. But no one asked if that development was good or appropriate – we drained off a lot of our water supply in the process and messed up the ecological system that provided a lot of the recharge. No one asked in the 1930 if this was a good idea.

Designing/building cities in the desert, designing systems that pump groundwater that does not recharge, or design systems that cannot be paid for by the community – we know what will happen at some point. Now that there are more people, conflicts become more likely and more frequent. Most times engineers are not asked to evaluate the unintended consequences of the projects they build. Only to build them to protect the public health safety and welfare while doing so, but from a specific vantage point.

So if you know a project will create a long-term consequence, what action should you take? So the question is whether there is a conflict between engineers meeting their obligations to the public and economic interests in such cases? Or should we just build, build, build, with no consideration of the consequences?

Climate Change, What Climate Change

Drought Discussions on Line

We are all aware of the major drought issues in California this year – it has been building for a couple years. The situation is difficult and of course the hope is rain, but California was a desert before the big water projects on the 1920s and 30s. Los Angeles gets 12 inches of rain, seasonally, so could never support 20 million people without those projects. The central valley floor has fallen over 8 feet in places due to groundwater withdrawals. Those will never come back to levels of 100 years ago because the change in land surface has collapsed the aquifer. But the warm weather and groundwater has permitted us to develop the Central Valley to feed the nation and world with produce grown in the desert. The development in the desert reminds me of a comment I saw in an interview with Floyd Dominy (I think), BOR Commissioner who said his vision was to open the west for more people and farming, and oversaw lots of projects to bring water to where there was none (Arizona, Utah). The problem is that the west never head much agriculture or population because it was hot, dry and unpredictable – hence periodic droughts should be no surprise – the reason they are a surprise is that we have developed the deserts far beyond their capacity through imported water and groundwater. Neither may be reliable in the long run and disruptions are, well, disruptive. Archaeologist Bryan Fagan traced the fall of Native American tribes in Arizona to water deficits 1000 years ago.

Yet policymakers have realized that civil engineers have the ability to change the course of nature, at least temporarily, as we have in the west, south, Florida. I often say that the 8th and 9th wonders of the world are getting water to LA over the mountains and draining the southern half the state of Florida. I have lived in S. Florida for 25+ years and am very familiar with our system. The difference though is that we have the surficial Biscayne aquifer and a rainy season that dumps 40 inches of rain on us and LA doesn’t (as a note of caution, for the moment we are 14 inches below normal in South Florida – expect the next drought discussion to ensue down here in the fall). The biggest problems with the Everglades re-plumbing are that 1) no one asked about unintended consequences – the assumption was all swamps are bad, neglecting impacts of the ecosystem, water storage, water purification in the swamp, control of feedwater to Florida Bay fisheries, ….. 2) one of those unintended consequences is that the recharge area for the Biscayne aquifer is the Everglades. So less water out there = less water supply along the coast for 6 million people 3) we lowered the aquifer 4-6 ft along the coastal ridge, meaning we let saltwater migrate inland and contaminate coastal wellfields 4) we still have not figured out how to store any of that clean water – billions o gallons go offshore every day because managing Lake Okeechobee and the upper Everglades was made much more difficult when the Everglades Agricultural Area was established on the south side of Lake Okeechobee, which means lots of nutrients in the upper Everglades, and a lack of place for the lake to overflow, which meant dikes, more canals, etc. to deal with lake levels.

The good news is that people only use 11% of the water in California and Florida, and that Orange County, CA and others have shown a path to some degree of sustainability (minus desal), but the real problem is water for crops and the belief that communities need to grow. When we do water intensive activities like agriculture or housing, in places where it should not be, it should be obvious that we are at risk. Ultimately the big issue it this – no policy makers are willing to say there is “no more water. You cannot grow anymore and we are not going to send all that water to Ag.” Otherwise, the temporary part of changing nature will come back to haunt us.

Water Use – does drought really tell us anything – or do we miss just the message?

Spring is in the air, at least in some places, so it gives us a chance to take stock of where we are after the winter. Boston actually is seeing the ground after record snow. The west is seeing lots of ground, even though some areas should not be seeing ground at this point. I recall the Colorado Rockies having snow at 8000 ft a couple years ago, but not this year. Some ski resorts in western Colorado never opened. Not a good sign. Snow was 10% of normal in parts of California which means the drought will continue. 12% in Oregon and Washington is some part – not good for places that rely on snow for water supplies. So the question is whether the current drought is the start of a longer climate driven issues and/or the result of where demands have permanently exceeded supplies? And if the latter is true, conservation is one option, but has obvious financial and supply limitations since urban use is less than 12% of water total use (agriculture is 40% and power plant cooling water is 39%).

Better management is part of a toolbox, but when the supply is finite, the economics says that costs will increase, shutting out certain sectors of the economy. This is where the “market system” theory of economics fails large sectors of the population – at some point finite supplies become available only to those who can afford to pay, but water is not one of those commodities that is a luxury – we need it to survive. Certainly the argument can be made that water is underpriced, but like energy, low water prices have helped fuel economic development while improving public health. It is a chicken/egg conundrum where the argument that conservation will solve all problems is not realistic, nor is using the market or curtailing economic activity. This is where the market fails and therefore governments have a role in insuring that all sectors are treated fairly and the commodity can be provided to all those in need of it – serving the public good. The public good or public welfare argument is often lost in the political dogma of today, but our forefathers had this figured out and designed regulations to insure distribution after seeing the problems that arose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. We have forgotten many of those lessons.

The public good or welfare does not mean unlimited distribution to areas that would otherwise be bereft of the commodity. The early engineers in Los Angeles realized that development could only continue if water was brought in. So massive water movement projects were developed. The economic benefit was the only consideration – the impacts of these changes were not considered. Likewise the Corps of Engineers was directed to drain the Everglades, but no one asked if this was a good idea or would have negative impacts. Loss of the Everglades permitted economic development that is southeast Florida – 40% of the economy of the state, but it impacted water supply and places millions are risk for future sea level rise impacts. Worse, agriculture was fostered in the upper Everglades as the federal government sold off the acreage to private interests cheaply to encourage sugar cane and winter vegetables. That agriculture is now planning to develop the Everglades if the property is not purchased by the state. But purchasing the property rights a prior error in consequences – it is likely in the public interest as an effort to restore water supplies in the Biscayne acquire that feed southeast Florida, and to increase water flows to retard saltwater migration in the southern Everglades. These are both ”sins” of the past, made with good intentions but with very little thought of consequences beyond the economic benefits. Both have resulted in water shortages in the areas they were meant to serve as climate patterns have changed.

The question is whether we continue to make these mistakes. Development in desert areas, areas known to be water poor, and deepening wells to get groundwater supplies who’s levels continue to decline are all poor long-term decision, despite the short-term potential gains. California farmers continue to deepening wells but those aquifers have a limit in depth. Deepening wells means those wells do not recharge (otherwise the aquifer levels would not continually decline). What happens when the wells run dry permanently? Clearly the sustainability criteria is not met.

Meanwhile lower aquifer can divert surface waters into the ground – not enough for full recharge, but perhaps enough to impact surface water flows to other farmers, potable water users, and ecosystems. Droughts are climate driven- and we have persevered droughts before, and will again. However in light of the California drought, perhaps we should all assess more closely the long-term trends – lowering groundwater, increasing demands, lessening availability and make better decisions on water use – not only in California but in many parts of the US and the world. Changing water use patterns is great, but it is just part of a larger issue — do we need to change our current behaviors – in this case water use – in certain areas? Are there just places we should not develop? Is there a limit to water withdrawals? And how do we deal with the economic losses that will come? All great question – but do we have the leadership in place to make the hard decisions?