Let’s start with the basic premise of this conversation – fracking is here to stay! It doesn’t matter how many petitions you get in the mail, fracking is going to continue because the potential for gas production from fracking and the potential to fundamentally change our energy future, near or long-term, far outweighs the risk or economic and security disruptions from abandoning fracking efforts. It looks like there is a lot of trapped gas, even if the well exponentially decay production in the first three years, although many well can be recovered by refracking. It is an issue that residents and utilities need to accept. The question is really how to assess the risks to water supplies from fracking and what is what can we do about it?

There are a number of immediate regulatory issues that should be pursued, none of which Vikram Rao (2010) suggests are truly deal killers. They start with the disclosure of the fracking fluids, which for most legitimate companies that are fracking are relatively benign (and do not include diesel fuel). Baseline and ongoing monitoring of formations above the extraction zones, and especially in water production zones is needed. Research on water quality treatment solutions is needed because t may be impossible to completely eliminate escaping gas is needed. Requirements to improve and verify well construction and cementing of formation is needed in all states (they are not now) and recycling frack water and brine should be pursued to avoid impacts on streams and wastewater plants, which limits the loss of water due to fracking operation and the potential for contamination of surface water bodies. It will be important to push for these types of regulations in states like Ohio and West Virginia that need jobs and are likely places for fracking to occur, but they are also likely places where there will be political pushback that is afraid of discouraging job investments, but in reality this is unfounded. The gas is there, so the fracking will follow. The question is will the states implement needed regulations to protect the public.

More interesting will be the ancillary issues associated with gas and wet gas. A lot of by products come from wet gas, like polyethylene which can be used as stock for a host of plastics. “Crakers” are chemical processing plants that are needed to separate the methane and other products. Where will those facilities be located, is an issue. Right now they are on the Gulf coast, which does not help the Midwest. Do we really need to ship the gas to Louisiana for processing or do we locate facilities where the gas and byproducts are needed (in the Midwest)? The Midwest is a prime candidate for cracker location, which will create both jobs as well as potential exports. Also stripping the gas impurities like ethane, DEM and others needs to occur.

So what do utilities need to look at the potential impacts on their water supplies and monitor. If the states will not make the fracking industry do it, we need to. Finding a problem from fracking after the fact is not helpful. We need to look at potential competition for water supplies, which is in part why recycling frack water brine is needed. Eliminating highly salty brine from going to a treatment plant or a water supply are imperatives. Sharing solutions to help treat some of these wastes may be useful – something we can help the industry with is treating water.

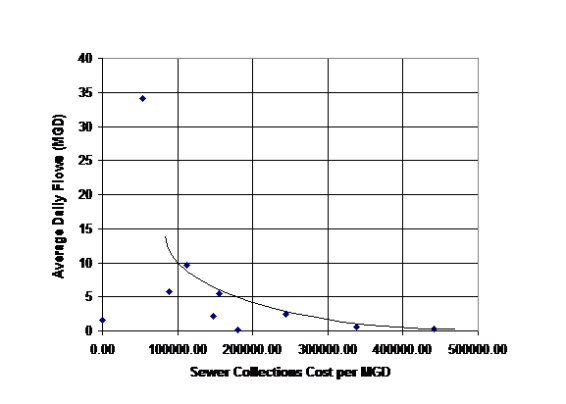

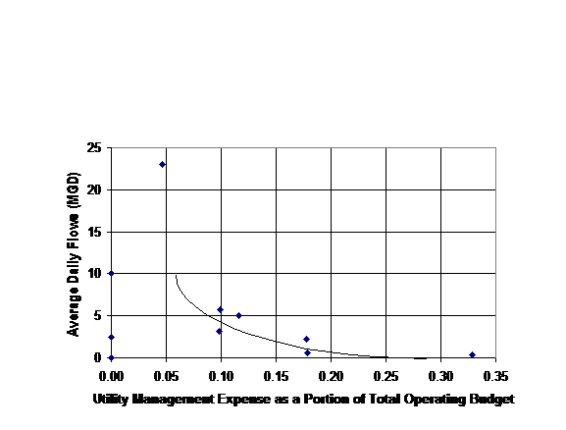

We also need to look at the processing plants. We need to be looking at the impact of these facilities in light of water and sewer demands (and limitations). Wet gas facilities will require water as will plastics and chemical plants. Historically a lot of these facilities were in the Midwest and the research and skill sets may still be present. How can these industries can be merged into current water/sewer scenarios without adverse impacts. Communities will compete for these facilities, but good decisions may dictate that vying is not the best way to locate a plant.

But there is another impact to utilities and that affects green technologies. The cost of gas is low and looks like it will remain low in the near future. Low gas prices mean that renewable solutions like solar and wind will be less attractive, especially if federal subsidies disappear. Wind is the largest addition to the power generation profile in the last 5 years, while many oil facilities changed to gas. Cheap gas may frustrate efforts to create distributed power options at water and wastewater treatment plants throughout the country which can directly benefit utilities, not just where fracking occurs. So we need to be cognizant of these cost issues as well. And you thought the fracking discussion might not affect you….