We have a lot of conversations about the impact of people on the ecosystem, the cost to reuse wastewater, competing water demands, water limited areas etc. All are valid issues to raise and since people control the outcomes in all of these situations, we need to be aware of consequences. So while Florida is a leader is wastewater reuse for irrigation, it is kinda cool to see what happens when we think outside the box. The Wakodahatchee wetland is a sewer treatment area created by Palm Beach County Utilities a number of years ago. This is reclaimed quality water placed into an area specifically designed to allow for nutrient removal and aquifer recharge. The County placed mosquitofish in the water to reduce mosquitos. Bluegills found there way. So did the turtles and alligators. But this is THE bird watching site in southern Palm Beach County. And it is located between the wastewater plant and a neighborhood. You can’t get parking easily. This is an example where looking at the bigger picture seems to have a positive effect on the community and the ecosystem as well. The birds don’t look unhappy.

management

And then there is Flint – A lesson on Why Politics and Money Should Never Trump Public Health

Speaking of water supply problems, welcome to Flint, Michigan. There have been a lot of coverage in the news about the troubles in Flint the last couple of months. However if you read between the lines you see two issues – first this is not new – it is several years old, going back to when the City’s water plant came back on line in May 2014. Second this was a political/financial issue not a public health issue. In fact, the political/financial goals appear to have been so overwhelming, that the public health aspects were scarcely considered. Let’s take a look at why.

Flint’s first water plant was constructed in 1917. The source was the Flint River. The second plant was constructed in 1952. Because of declining water quality in the Flint River, the city, in 1962, had plans to build a pipeline from Lake Huron to Flint, but a real estate scandal caused the city commission to abandon the pipeline project in 1964 and instead buy water from the City of Detroit (source: Lake Huron). Flint stopped treating its water in 1967, when a pipeline from Detroit was completed. The City was purchasing of almost 100 MGD. Detroit declared bankruptcy. The City of Flint was basically bankrupt. Both had appointed receivers. Both receivers were told to reduce costs (the finance/business decisions). The City of Flint has purchased water for years from Detroit as opposed to using their Flint River water plant constructed in 1952. The Flint WTP has been maintained as a backup to the DWSD system, operating approximately 20 days per year at 11 MGD.

The City of Flint joined the Karegnondi Water Authority (KWA) in 2010. The KWA consists of a group of local communities that decided to support and fund construction of a raw water pipeline to Lake Huron. The KWA was to provide the City of Flint Water Treatment Plant with source water from Lake Huron. An engineer’s report noted that a Genesee County Drain Commissioner stated that one of the main reasons for pursuing the KWA supply was the reliability of the Detroit supply given the 2003 power blackout that left Flint without water for several days. Another issue is that Flint no say in the rate increases issued to Flint by Detroit. Detroit’s bankruptcy may also have been a factor given the likelihood of increased prices. While discussion were ongoing for several years thereafter, the Detroit Free Press reported a 7-1 vote in favor of the KWA project by Flint’s elected officials in March, 2013. The actual agreement date was April 2013. The cost of the pipeline was estimated to be $272 million, with Flint’s portion estimated at $81 million.

The City of Detroit objected due to loss of revenues at a time when a receiver was trying to stabilize the city’s finances (in conjunction with the State Treasurer). In February 2013, the engineering consulting firm of Tucker, Young, Jackson, Tull, Inc. (TYJT), at the request of the State Treasurer, performed an analysis of the water supply options being considered by the City of Flint. The preliminary investigation evaluated the cost associated with the required improvements to the plant, plus the costs for annual operation and maintenance including labor, utilities, chemicals and residual management. They indicated that the pipeline cost was likely low and Flint’s obligation could be $25 million higher and that there was less redundancy in the KWA pipeline than in Detroit’s system. In 2013, the City of Detroit made a final offer to convince Flint to stay on Detroit water with certain concessions. Flint declined the final Detroit offer. Immediately after Flint declined the offer, Detroit gave Flint notice that their long-standing water agreement would terminate in twelve months, meaning that Flint’s water agreement with Detroit would end in April 2014 but construction of KWA was not expected to be completed until the end of 2016.

It should be noted that between 2011 and 2015, Flint’s finances were controlled by a series of receivers/emergency managers appointed by the Governor. Cutting costs was a major issue and clearly their directive from the Governor. Cost are the major issue addressed in the online reports about the issue. Public health was not.

An engineering firm was hired as the old Flint River plan underwent $7 million in renovations in 2014 to the filters to treat volumes of freshwater for the citizens. The project was designed to take water from the Flint River for a period of time until a Lake Huron water pipeline was completed. The City of Flint began using the Flint River as a water source in May of 2014 knowing that treatment would need to be closely watched since the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality in partnership with the U.S. Geological Survey, and the City of Flint Utilities Department conducted a source water assessment and determined the susceptibility of potential contamination as having a very high susceptibility to potential contaminant sources (take a look at this photo and see what you think).

Flows were designed for 16 MGD. Lime softening, sand filters and disinfection were in place. Everything sounded great. But it was not. Immediately, in May and August of 2014, TTHM samples violated the drinking water standards. This means two things – total organic carbon (TOC) in the water and additional chlorine being added to disinfect and probably reduce color caused by the TOC. Softening does not remove TOC. Filtration is not very effective either. High concentration usually needs granular activated carbon, ion exchange or membranes. The flint plant had none of these, so the carbon staying in the water. To address the TTHM issue, chlorine appears to have been reduced as the TTHM issue was in compliance by the next sampling event in Nov 2014. However, in the interim new violations included a total coliform and E. coli in August and September of 2014, and indication of inadequate disinfection. That means boil your water and lots of public outcry. The pH, salinity (salt) and other parameters were reported to be quite different than the Detroit water as well. A variable river system with upstream agriculture, industry and a high potential for contamination, is not nearly as easy to treat as cold lake water. These waters are very different as they City was to find. What this appears to indicate is that the chemistry profile and sampling prior to conversion and startup does not appear to have been fully performed to identify the potential for this to occur or this would have been discovered. This is now being suggested in the press.

The change in water quality and treatment created other water quality challenges that have resulted in water quality violations. Like most older northern cities, the water distribution system in almost 100 years old. As with many other municipalities at the time, all of the service lines from the cast iron water mains (with lead joints) to end users homes were constructed with lead goosenecks and copper lines. Utilities have addressed this with additive to prevent corrosion. In the early 1990s water systems were required to comply with the federal lead and copper rule. The concept was that on the first draw of water in the morning, the lead concentration should not exceed 0.015 mg/L and copper should not exceed 1.3 mg/L. Depending on the size of the utility, sampling was to be undertaken twice and a random set of hoses, with the number of samples dependent on the size of the system. The sampling was required to be performed twice, six months apart (note routine sampling has occurred since then to insure compliance). Residents were instructed on how to take the samples, and results submitted to regulatory agencies. If the system came up “hot” for either compound, the utility was required to make adjustments to the treatment process. Ideally water leaving the plant would have a slightly negative Langlier saturation index (LSI) and would tend to slightly deposit on pipes. Coupon tests could be conducted to demonstrate this actually occurred. As they age, the pipes develop a scale that helps prevent leaching. Most utilities tested various products. Detroit clearly did this and there were no problems. Flint did not.

The utility I was at was a perfect 100% non-detects the first time were tested. We had a few detections of lead and copper in samples the second time which really bothered me since the system was newer and we had limited lead in the lines. I investigated this and found that the polyphosphate had been changed because the County purchasing department found a cheaper product. I forced them to buy the old stuff, re-ran the tests and was again perfect. We instructed our purchasing department that saving a few bucks did not protect the public health, but the polyphosphate product did. Business and cost savings does not trump public health! Different waters are different, so you have to test and then stay with what works.

Now fast forward to Flint. They did not do this testing. The Flint River water was different that Detroit’s. Salinity, TOC, pH and overall quality differed. Accommodations were not made to address the problem and the state found no polyphosphates were added to protect the coatings. Veolia reported that the operations needed changes and operators needed training. Facilities were needed to address quality concerns (including granular activated carbon filter media). As a result the City appears to have sent corrosive water into the piping system, which dissolved the scale that had developed over the years, exposing raw metal, and created the leaching issue. Volunteer teams led by Virginia Tech researchers reported found that at least a quarter of Flint households have levels of lead above the federal level of 15 ppb, and as high as 13,200 ppb. Aging cast-iron pipe compounded the situation, leading to aesthetic issues including taste, odor and discoloration that result from aggressive water (brown water). Once the City started receiving violations, public interest and scrutiny of the drinking water system intensified.

The City Commission reportedly asked the receiver to switch back to Detroit water, but that request was initially rebuffed and the damage to pipes continued. Finally in October 2015, the water supply was switched back to Detroit and the City started adding additional zinc orthophosphate in December 2015 to facilitate the buildup of the phosphate scale eroded from the pipes by the Flint River water. But that means the pipes were stable, then destabilized, now destabilized again by the switch back. It will now take some time for the scale to rebuild and to lower lead levels, leaving the residents of Flint at risk because of a business/finance/political decision that had not consideration of public health impacts. And what is the ultimate fate of the KWA pipeline?

Just when things were starting to look up (?), in January 2016, a hospital in Flint reported that low levels of Legionnaires’ disease bacteria were discovered in the water system and that 10 people have died and another 77 to 85 affected. From the water system? A disinfection problem? Still TOC in the water? The lawsuits have begun but where does the problem lie? Let’s look at Walkerton Ontario for guidance in the aftermath of their 2000 incident.

First it is clear that public health was not the primary driver for the decisions. Treating water is not as simple as cost managers think. You need to understand what water quality, piping quality and stabilization you have and address the potential issues with new water sources. Membrane systems are very familiar with these challenges. Cost cannot be the driver. The Safe Drinking Water Act does not say cost is a consideration you use to make decisions. Public health is. So the initial decision-making appears to have been flawed. Cost was a Walkerton issue – cost cannot be the limiting factor when public health is at risk.

The guidance from consultants or other water managers is unclear. If the due diligence of engineers as to water quality impacts of the change in waters was not undertaken, the engineering appears to have been flawed. If the engineer recommended, and has lots of documentation saying testing should be done, but also a file full of accompanying denials from the receivers, another flawed business decision that fails the public health test. If not, I see a lawsuit coming against the consultants who failed in their duty to protect the public health, safety and welfare.

The politics is a problem. A poor community must still get water and sewer service. Consultants that can deal with rate and fee issues should be engaged to address fairness and pricing burdens. Was this done? Or was cutting costs the only goal? Unclear. The politics was a Walkerton issue.

Was the water being treated properly? Water quality testing would help identify this. Clearly there were issues with operations. Telling the state phosphates were used when they were not, appears to be an operations error. Walkerton also had operations issues as well. A major concern when public health is at risk. Veolia came to a similar conclusion.

The state has received its share of blame in the press, but do they deserve it? The question I have is what does the regulatory staff look like? Has it been reduced as the state trims its budget? Are there sufficient resources to insure oversight of water quality? The lack of provincial resources to monitor water quality was an issue in Walkerton – lack of oversight compounded local issues. That would then involve the Governor and Legislature. Politics at work. Likewise was there pressure applied to make certain decisions? If so, politics before public heath – a deadly combination.

So many confounding problems, but what is clear is that Flint is an example of why public utilities should be operated with public health at the forefront, not cost or politics. Neither cost of politics protect the public health. While we all need finances to pay for our needs, in a utility, money supports the operations, not controls it. We seems to have that backward. Private entities look sat controlling costs. Public agencies should look at public service first; cost is down the list. We need the operations folks to get the funds needed to protect the public health. And then we need to get the politicians to work with the staff to achieve their needs, not limit resources to cut costs for political gain. Ask the people in Flint.

So is Flint the next Walkerton? Will there be a similar investigation by outside unconnected people? Will the blame be parsed out? Is there a reasonable plan for the future? The answers to these questions would provide utilities with a lot of lessons learned and guidance going forward and maybe reset the way we operate our utilities. Happy to be a part of it if so!

Water Quality and Watersheds – What Could Possibly go Wrong?

In the last blog we talked about a side issue: ecosystems, bison, wolves, coyotes and the Everglades, which seem very distant form our day-to-day water jobs, but really are not. So let’s ask another, even more relevant issue that strikes close to home. Why is it that it is a good idea to store coal ash, mine tailings, untreated mine waste, garbage, and other materials next to rivers? We see this over and over again, so someone must think this is brilliant. It cost Duke Energy $100 million for the 39,000 tons of coal ash and 24 MG of wastewater spilled into the Dan River near Eden NC in 2014. In West Virginia, Patriot Coal spilled 100,000 gallons of coal slurry into Fields Creek in 2014, blackening the creek and impacting thousands of water supply intakes. Fines to come. Being a banner year for spills, again in West Virginia, methylcyclohexamethanol was released from a Freedom Industries facility into the Elk River in 2014, contaminating the water supply for 300,000 residents. Fines to come, lawsuits filed. But that’s not all. In 2008, an ash dike ruptured at an 84-acre solid waste containment area, spilling material into the Emory River in Kingston TN at the TVA Kingston Fossil Plant. And in 2015, in the Animas River in western Colorado, water tainted with heavy metal gushed from the abandoned Gold King mining site pond into the nearby Animas River, turning it a yellow for dozens of miles crossing state lines.

Five easy-to-find examples that impacted a lot of people, but it does not address the obvious question – WHY are these sites next to rivers? Why isn’t this material moved to more appropriate locations? It should never be stored on site, next to water that is someone else’s drinking water supply. USEPA and state regulators “regulate” these sites but regulation is a form of tacit approval for them to be located there. Washington politicians are reluctant to take on these interests, to require removal and to pursue the owners of defunct operations (the mine for example), but in failing to turn the regulators loose to address these problems, it puts our customers at risk. It is popular in some sectors to complain about environmental laws (see the Presidential elections and Congress), but clearly they are putting private interests and industry before the public interest. I am thinking we need to let the regulators do their job and require these materials to be removed immediately to safe disposal. That would help all of us.

Wild Places, WIldlife and Water

Most water suppliers realize that the more natural their land is upstream of their water supplies, the less risk there likely is for their customers. Under the source water protection programs that state, local officials and water utilities implement, the concept is to keep people related activities out, and let the natural forests and landscapes remain. For the most part the natural areas support only a limited amount of wildlife (sustainable) and thereby there natural systems are attuned to compensate for the natural pollutant loads, sediment runoff, ash, detrital matter, etc., that might be created through natural processes. For thousands of years these systems operated sustainably. When people decide there needs to be changes, it seems like the unanticipated consequences of these actions create more problems. Now many of these same ecosystems do not work sustainably and water quality has diminished, increasing the need for treatment and the risks of contamination to the public. It would be better, but decidedly less popular on certain fronts, to provide more protection to natural systems that extend into watersheds (which is most of them), not less.

So this leads to a series of questions that go to the greater questions about natural environments:

Is it really necessary to cull the small Yellowstone bison herd by 1000? What do bison have to do with watersheds? Well, the bison create much less damage to grasslands and underlying soil than cattle due to the size of their hooves. An argument is that we need to cull the herd because they transmit disease to cattle, but Brucellosis has never been demonstrated to move from bison to cattle, so disease is not an answer. What is really happening is that there is competition between buffalo and cattle for grazing. Competition with cattle means that the cattle are on public property, not private ranch lands, and the cattle trample the public lands which creates the potential for soil erosion and sediment runoff. So I am thinking water folks should be siding with the bison. Of course without wolves, there is no natural predator for bison, which raises a different sustainability problem, so maybe instead of killing them, we move them to more of their native ranges – maybe some of those Indian reservation might want to restart the herds on their lands? That might be good for everyone, water folks included.

Part 2 – is it necessary to continue to protect wolves or should we continue to hunt them in their native ranges? Keep in mind wolf re-introduction efforts are responsible for most of the wolf populations in the US, specifically in the Yellowstone area. Without wolves, there is no control of large grazing animal populations (see bison above, but also elk and deer), and there is a loss of wetland habitat because the elk eat the small shoots used by beavers to build dams and trap sediment. Eliminating wolves has been proven to create imbalance. Wolves = sediment traps = better water quality downstream. Sounds like a win for everyone. (BTW there is a program in Oregon to protect wolves and help ranchers avoid periodic predation of calves by wolves so they win too).

Part 3 – Is it really necessary to kill off coyotes in droves? The federal government kills thousands of coyotes and hunters and others kill even more. This is a far more interesting question because it leads to one of those unintended consequences. !100+ years ago people decided wolves were bad (we still have this issue ongoing – see above). So we eradicated wolves. No wolves means more rodents, deer, elk, etc. which mean less grass, less aspens and less beavers, which means more runoff which does not help water suppliers. It also means more coyotes, because there is more food for the coyotes. Interesting that coyotes have pretty much covered the entire US, when their ranges were far more limited in the past. Coyotes are attracted to the rodents and rabbits. But the systems are generally not sustainable for coyotes because there is not enough prey and there is no natural control of the coyotes – again, see wolves above. A Recent Predator defense report indicates that culling coyotes actually increases coyote birth rate and pushes them toward developed areas where they find cats and small dogs, unnatural prey. Not the best solution – unintended consequences of hunting them on more distant land pushes them into your neighborhood. Not the consequence intended. So maybe we keep the small dogs and cat inside at daybreak and nightfall when the coyotes are out and let them eat the rats and mice that the cats chase and once consumed they go away. Coyotes need to eat grazers and rodents but you need the right mix or the grazers overgraze, which leads to sediment runoff issues – which is bad for us. That also seems like a win.

Everglades restoration is a big south Florida issue. The recharge area for the Biscayne aquifer is the Everglades. So water there seems like a win for water suppliers? So why aren’t we the biggest Everglades advocates out there? Still searching for that answer, but Everglades restoration is a win for us and a win for a lot of critters. Federal dollars and more federal leadership on restoration is needed. Which leads to ….

Do we need more, not less management of federal lands? Consider that the largest water manager in the west is the federal government, which has built entire irrigation systems to provide water to farmers who grow crops in places that are water deficient. Those farms then attract people to small towns that consume more of the deficient water. Then people lobby to let cattle graze on those public lands (see bison above), timber removal – which increases sediment erosion, or mining (what could possible go wrong there?). So since the federal government manages these lands, wouldn’t better regulations and control to keep the federal properties more protected benefit water users and suppliers? Contrary to the wishes of folks like the guys holed up in a federal monument in Oregon, or the people who have physically attacked federal employees in Utah and Nevada, more regulations and less freedom is probably better in this situation for the public good. If we are going to lease public lands (and most lands leased are leased to private parties for free or almost free), and there should be controls on the activities monitoring for compliance and requirements for damage control caused by those activities. There should be limits on grazing, timber and mining, and monitoring of same. Lots of monitoring. It is one of the things government really should do. And we need it to protect water users downstream. Again a win for water suppliers.

So as we look at this side issue, ecosystems, bison, wolves, coyotes and the Everglades seem very distant from our day-to-day water jobs. But in reality they are not. We should consider the impacts they might have on water supply, keeping in mind natural system decisions are often significantly linked to our outcomes, albeit the linkage is not always obvious.

Economics – Are things Really Better?

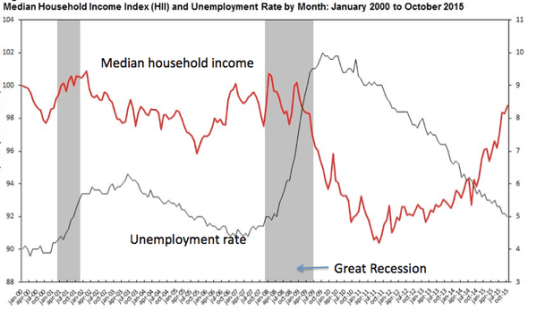

My cousin once asked me what I thought about deciding on who to vote for for President might be best done when evaluating how well your 401K or investments did. Kind of an amusing thought. In that vein the decisions might be very different than they were. Clearly your 401k did with with Clinton. The economy was flat for George W. Bush, and the end of his term was the Great Recession. Reagan’s first term was flat. We all know about George H.W. Bush. Interesting thoughts. Not so good. So what about the last 8 years? But is raises a more interesting issue. So don’t get me wrong, this blog is not intended to lobby for any candidate (and Obama can’t run), but it is interesting to look at the last 8 years. They have been difficult. The economy responded slowly. Wages did not rebound quickly. But in comparison to 2008 are we better off?

The question has relevance for utilities because if our customers are better off, that gives us more latitude to do the things we need – build reserves (so we have funds for the next recession), repair/replace infrastructure (because unlike fine wine, it is not improving with age), improve technology (the 1990s are long gone), etc., all things that politicians have suppressed to comport with the challenges faced by constituents who have been un- or under-employed since 2008.

Economist Paul Krugman makes an interesting case in a recent op-ed in the New York times: (http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/01/13/yes-he-did/?module=BlogPost-Title&version=Blog%20Main&contentCollection=Opinion&action=Click&pgtype=Blogs®ion=Body). Basically he summarizes the figure below which shows that unemployment is back to pre-2008 levels, and income is back to that point. Some income increase would have been good, but this basically tracks with the Bush and Reagan years for income growth – flat. So the question now is in comparison to 2008 are we worse off that we were? And if not, can we convince leaders to move forward to meet our needs? Can we start funding some of the infrastructure backlog? Can we modernize? Can we create “smarter networks?” Can we adjust incomes to prevent more losses of good employees? Can we improve/update equipment? All issues we should contemplate in the coming budget.

Limited Groundwater

Over the holidays there were a couple articles that came out about groundwater issues in the US, mostly from the declining water level perspective. I also read a paper that suggested that rising sea level had a contribution from groundwater extraction, and of course USGS has maps of areas where the aquifer have collapsed as a result of overpumping. In 2009 USGS published a report that showed a large areas across the country with this issue. The problem is that of the 50,000 community water systems in the US, 500 serve over 50% of the population, and most of them are surface water plants. There are over 40,000 groundwater systems, but most are under 500 customers. Hence, groundwater is under represented at with the larger water associations because the large utilities are primarily surface water, while the small systems are groundwater. AWWA has difficulty reaching the small systems while RWA and NGWA reach out to them specifically. But the small utility seems more oriented to finding and producing water and operating/maintaining/drilling wells than the bigger impact of groundwater use. It is simply a matter of resources. I ran a system like that in North Carolina, and just getting things done is a huge issue. A couple of my medium size utility clients have the same problem.

Over the holidays there were a couple articles that came out about groundwater issues in the US, mostly from the declining water level perspective. I also read a paper that suggested that rising sea level had a contribution from groundwater extraction, and of course USGS has maps of areas where the aquifer have collapsed as a result of overpumping. In 2009 USGS published a report that showed a large areas across the country with this issue. The problem is that of the 50,000 community water systems in the US, 500 serve over 50% of the population, and most of them are surface water plants. There are over 40,000 groundwater systems, but most are under 500 customers. Hence, groundwater is under represented at with the larger water associations because the large utilities are primarily surface water, while the small systems are groundwater. AWWA has difficulty reaching the small systems while RWA and NGWA reach out to them specifically. But the small utility seems more oriented to finding and producing water and operating/maintaining/drilling wells than the bigger impact of groundwater use. It is simply a matter of resources. I ran a system like that in North Carolina, and just getting things done is a huge issue. A couple of my medium size utility clients have the same problem.

The bigger picture may contain the largest risk. Changing water supplies is a high cost item. We have seen a couple examples (surface water) as a result of drought. We saw Wichita Falls and Big Springs TX go the potable reuse route due to drought. California is looking at lots of options. Both have had rain lately (Wichita Falls discontinued the potable reuse when the reservoir got to 4% of capacity). Great, but someone is next. Droughts come and go, and the questions is how to deal with them.

Groundwater supposedly is a drought-proof problem, but is it? Groundwater has been a small utility solution, as it has been for agriculture. But aquifer require recharge and water limited areas do not have recharge. The result is a bigger problem – overpumping. Throughout the west/southwest, Plains states, upper Midwest (WI, MN, IA), southeast (SC, NC), we see this issue. Most of these areas have limited surface water so never developed much historically. Rural electrification changes that because it made is easy to put in an electric pump to pull water out of the ground in areas that never had a lot of water on the surface, and hence were not farmed much. Pumps made is easier to farm productively, which led to towns. However, our means to assess recharge are not very good, especially for confined aquifers. The lowering water levels USGS and state agencies see is an indication that recharge is normally over estimated giving a false picture of water availability. If your aquifer declines year after year, it is not drought – it is mining of the aquifer. You are sucking it dry like the eastern Carolinas did. But, like many negative things, there is a lack of willingness to confront the overpumping issue in many areas. There are many states with a lack of regulations on groundwater pumping. And I still think groundwater modeling use is limited to larger utilities, when smaller, rural systems may be most in need of it due to competing interests.

Concurrently, I think there is a tendency to oversell groundwater solutions (ASR, recharge), groundwater quality and the amount of available water (St George, UT). Easy, cheap, limited treatment should not be the only selling point. That leads to some curious decisions like some areas of California north of LA the utilities do not treat hard groundwater – then tell residents they cannot use softeners because of the salt in the wastewater prevents it from being used for reuse. The reason they do not treat – cost, but it makes things difficult for residents. The fact is we do not wish to confront is the realization that for many places, groundwater should probably be the backup plan only, not the primary source.

That leads to the question – what do we do about it when every politician’s goal is for their community to grow? For every farmer to grow more crops? But can they really grow sustainably? DO we not reach a point where there are no more resources to use? Or that the costs are too high? Or that competition become unruly? The growth and groundwater use ship is sailing, but in to many cases they do not see the rocks ahead.

10 Questions for 2016

So everyone is doing their Top 10 questions for 2016 (although with David Letterman off the air, perhaps less so), I figured why not? So it the vein of looking forward to 2016, let’s ponder these issues that could affect utilities and local governments:

- How wild, or weird will the Presidential election get? And part b, what will that do to America’s status in the world? Thinking it won’t help us. Probably won’t help local governments either.

- Will the economic recovery keep chugging along? Last time we had an election the economy tanked. Thinking a major change in direction might create economic uncertainty. Uncertainty (or panic) would trickle down. Status quo, probably keeps things moving along. .

- What will the “big” issue be in the election cycle and who will it trickle down to local governments and utilities? In 2008 it was the lack of health care for millions of Americans and the need for a solution. Right after the election we got the Great Recession so most people forgot about the health care crisis until the Affordable are Act was signed into law. And then ISIS arose from a broken Iraq and Arab summer. None helped local governments.

- What are we going to hear about the 20 richest Americans having more assets than the bottom 150 million residents? 20 vs 150,000,000. And while we are at it, the top 0.1% have more assets than the bottom 90%, the biggest disparity since the 1920s. While we will decide that that while hard work should be rewarded, the disparity is in part helped by tax laws, tax shelters, lobbying of politicians, etc. as Warren Buffett points out, indicate a discussion about tax laws will be heard. Part b – if we do adjust the tax laws, how will we measure how much this helps the bottom 99.9%?

- What will be the new technology that changes the way we live? Computers will get faster and smaller. Phones are getting larger. Great, but what is the next “Facebook”? By the way the insurance folks are wondering how the self driving car will affect the insurance industry. So reportedly is Warren Buffett. Watch Mr. Buffett’s moves.

- Along a similar vein, will the insurance industry start rethinking their current risk policies to look at longer term as opposed to annual risk? If so what does that mean for areas where sea levels are rising? The North Carolina coast, where sea level rise acceleration is not permitted as a discussion item could get tricky.

- Will unemployment (now 5%) continue to fall with associated increases in wages? Will that help our constituents/customers? Will people use more water as a result?

- Where is the next drought? Or flood? And will the extremes keep on coming? Already we have record flooding in the Mississippi River in December – not March/April? Expect February to be a cold, snowy month. IT is upper 80s here. Snowing in the Colorado Rockies.

- Will we continue to break down the silos between water “types” for a more holistic view of water resources? We have heard a bunch on potable reuse systems. More to come there, especially with sensors and regulations. But in the same vein, will we develop a better understanding of the link between ecosystems and good water supplies, and encourage lawmakers to protect the wild areas that will keep drinking water cleaner?

- Will we get water, sewer, storm water, etc. customers to better understand the true value of water, and therefore get their elected official on board with funding infrastructure neglect? And will that come as a result of better education, a better economy, breaking down those silos, drought (or floods), more extreme event, more breaks or something else?

Happy New Year everyone. Best to all my friends and followers in 2016!

New Website and New Study Coming

For the new year, my PUMPS website (not this site) will be undergoing reconstruction. It has been a few years and some things are out of date. Instead the focus will be more on rate studies, financial planning and asset management as opposed to all the other issues (like publications). I will have a separate website for me, with all that stuff since some folks have hit the website looking for it. My main goal is to partner with some folks and try to help smaller utilities with financial and management issues. I will be adding work products, including the asset management stuff we are doing in Dania Beach and Davie. My hope is I energize PUMPS a bit. At the same time via FAU, we will be developing a study of utility costs and revenues since 2005, with emphasis on the impact of the 2008-2009 Recession. This will be instructive – and be an update to the 1997 and 199 studies I did (hard to believe they were so long ago). We will be looking nationally, as well as at different types of treatment, location and size. The idea will be to develop some tools to help utilities benchmark where they are in the bigger picture, and to help with identifying trends and potential missing issues. COnncection rates and asset is improtant to insure hte timely renewal and repalcement of critical infrastrucutre. After all, the people who get fired when things go wrong with a utility are not the politicians – its us!. I will be solicitng (or my studnet will) data from over 300 utilities across the country. If you are interested, or have clients who might be, let me know. I have tnatively discussed publication with AWWA – but it won’t jsut be water. Resue, wastewater etc will be included. Should be fun! Look for the results next summer!!

Federal money – just for giggles

How much money goes to the states from the Federal government? Ever wonder about that? And how do we react? We talk about the need to tighten the federal spending so we keep cutting back on the Superfund cleanup monies ($1 billion/yr), the State Revolving Fund loan system ($2.35 billion/yr), and under $2 billion/yr for clean energy systems. We are concerned about the projected increase of $66 billion/yr for the Affordable Care Act. But these sums are just a tiny component for the federal budget, which is dwarfed by the $3.1 trillion sent to the states during its 2013 fiscal year. So what are these funds? Retirement benefits, including Social Security and disability payments, veteran’s benefits; and other federal retirement and disability payments account for over 34% of these payments. Medicare in another 18%. Food assistance, unemployment insurance payments, student financial aid, and other assistance payments account for another 9%. Another 16% is for grants to state and local governments for a variety of program areas such as health care (half the amount is Medicaid), transportation, education, and housing and research grants. All the SRF and grant monies are in this 16%. Those water programs are barely visible in this picture. Contracts for purchases of goods and services for military and medical equipment account for another 13%, while smallest amount – salaries and wages for federal employees is 10%. Keep in mind that federal employees have dropped from nearly 7 million to 4.4 million since 1967. No federal employment expansion going on there.

So how much does this affect the states? Federal funds account for about 19 of the total gross domestic product of the US, a number that has been relatively consistent (within a few percentage points) for years. That is below its all-time highs, and about typical over the past 30 years. Figure 1 from a PEW report shows that federal funds are greater than 22% of the GDP in most southern states (which interestingly enough have the people that complain the most about the federal government intrusion), while the Plains states, Midwest, northeast and the west coast are generally below average, and the two coasts, especially complain the least. Mississippi, Virginia and New Mexico all top 30%.

So let me see if I have this right – those that pay the least, but get the most, complain the most about their benefactors, and those that pay the most, but collect less, complain less. That is the message! What is WRONG with that picture? And those people? The problem is I see it every day at the local level and it is truly baffling. It means that somehow our politics gotten so out of whack that those in need the most, seem to continue to vote against their best interests? Marketing clearly is a problem but are we fooled that easily. A message that distracts from the reality is obvious, but this continuing trend is just truly weird. No wonder it is so hard to accomplish things.

On Taxes and Fees – Is starving Government the Answer?

Most states were doing pretty well before the 2008 recession hit, but that ended in 2009. Most states had to make extremely difficult cuts or raise taxes, which was politically unacceptable. Of course invested pension systems received a lot of attention as their value dropped and long term sufficiency deteriorated, which was fodder for many changes in pensions, albeit not how they were invested. The good news is a lot of them came back in the ensuing 5 years, but 2015 may be different. A number of states have reported low earnings in 2015 and whether this may be the start of another recession. The U.S. economy has averaged a recession every six years since WWII and it has been almost seven years since the last contraction. With China devaluing their currency, this may upset the economic engine. At present there are analysts on Wall Street who suggest that some stocks may be overvalued, just like in 1999. If so, that does not bode well states like Illinois, Kansas, New Jersey, Louisiana, Alaska and Pennsylvania that are dealing with significant imbalances between their expenses and incomes. Alaska has most of its revenue tied to oil, so when oil prices go down (good for most of us), it is a huge problem for Alaska that gives $2200 to every citizen in the state. An economic downturn portends poorly for the no tax, pro-business experiment in Kansas that has been unsuccessful in attracting the large influx of new businesses, or even expansion of current ones. California and next door Missouri, often chided by Kansas lawmakers as how not to do business, outperform Kansas.

Ultimately the issue that lawmakers must face at the state and as a result the local level is that tax rates may not be high enough to generate the funds needed to operate government and protect the states against economic down turns. There is a “sweet spot” where funds are enough, to deal with short and long term needs, but starving government come back to haunt these same policy makers when the economy dips. It would be a difficult day for a state to declare bankruptcy because lawmakers refuse to raise taxes and fees.