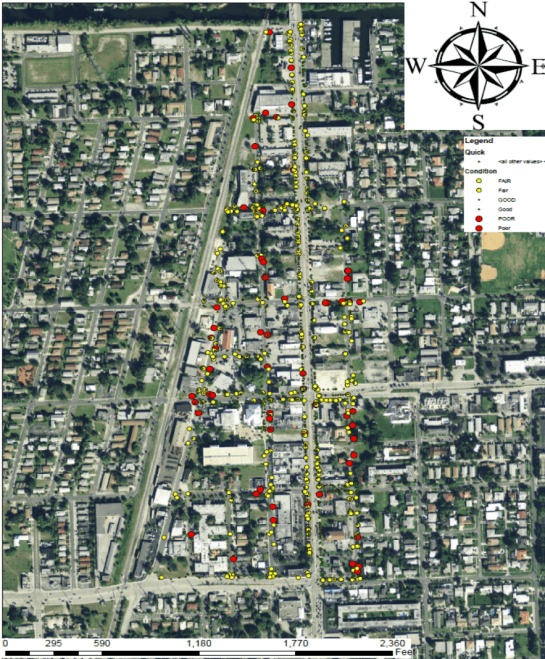

An asset management program should be developed accordingly to the client’s goals and objectives. It consists of determining the selected area of study, type of system and the quality of data used for evaluation. Before a condition assessment can be determined, an inventory of assets needs to be established – maps, etc. are helpful. So now you have a map of your water and sewer system and you want to develop a useful system for asset management. Depending on the accuracy wanted, the data can be gathered in many ways ranging from onsite field investigation which could take a lot of time, to using existing maps, using maps while verifying the structures using aerial photography and video, or field investigations. But most local governments still lack data. You cannot dig up pipe, or do a lot of destructive testing on buried infrastructure. So what to do?

The reality is that you have a lot more data than one thinks. For one thing, most utilities have a pretty good idea about the pipe materials. Worker memory can be very useful, even if not completely accurate. In most cases the depth of pipe is fairly similar – the deviations may be known. Soil conditions may be useful – there is an indication that that aggressive soil causes more corrosion in ductile iron pipe, and most soil information is readily available. Likewise tree roots will wrap around water and sewer pipes, so their presence is detrimental. Trees are easily noted from aerials. Likewise road with truck traffic create more vibrations on roads, causing rocks to move toward the pipe and joints to flex. So with a little research there are at least 5 variables known. If the break history or sewer pipe condition is known, the impact of these factors can be developed via a linear regression program. That can then be used as a predictive tool to help identify assets that are mostly likely to become a problem. We are working on such an example now, but suspect that it will be slightly different for each utility. Also, in smaller communities, many variables (ductile iron pipe, pvc pipe, soil condition…) may be so similar that differentiating would be unproductive. That also remains to be seen, which brings up another possible variable- the field perception – what do the field crews recall about breaks? Are there work orders? If so do they contain the data needed to piece together missing variables that would be useful to add to the puzzle?

After all we want to avoid this before it happens….

I have a question – what was the impact of the 2008 economic crisis on water and sewer infrastructure funding? I have a hypothesis – the amount of monies transferred to non-water and sewer operations increased. Is the hypothesis true?

I have a question – what was the impact of the 2008 economic crisis on water and sewer infrastructure funding? I have a hypothesis – the amount of monies transferred to non-water and sewer operations increased. Is the hypothesis true? Curtailed water use and conservation are common topics of conversation in areas with water supplies limitations. As drought conditions worsen, the need for action increases, so when creating a regulatory framework, or when trying to measure water use efficiency, water supply managers often look for easily applied metrics to determine where water use can be curtailed. Unfortunately, the one-size-fits-all mentality comes with a potential price of failing to fully grasp the consequences decision-making based on such metrics.

Curtailed water use and conservation are common topics of conversation in areas with water supplies limitations. As drought conditions worsen, the need for action increases, so when creating a regulatory framework, or when trying to measure water use efficiency, water supply managers often look for easily applied metrics to determine where water use can be curtailed. Unfortunately, the one-size-fits-all mentality comes with a potential price of failing to fully grasp the consequences decision-making based on such metrics.

A week or so ago, on a Sunday afternoon, I flew across Middle America to Colorado for a meeting and was again struck by the crop circles that dominate the landscape west of the Mississippi River. They are everywhere and are a clear sign of unsustainable groundwater use. I recently participated in a fly in event for National Groundwater Association in Washington DC, where several speakers, including myself, talked about dwindling groundwater levels and the impact of agriculture, power and economies. The impact is significant. Dr. Leonard Konikow, a recently retired USGS scientist, noted that he thinks a portion of sea level rise is caused by groundwater running off agriculture and from utilities and making its way to the ocean. He indicated that 5% of SLR each year was caused by groundwater runoff, and has upped his estimates in the past 10 years to 13%. This is because it is far easier for water to runoff the land than seep into rocks, especially deep formations that may take many years to reach the aquifer. And since ET can reach 4 ft below the surface, many of the western, dry, hot areas lose most of this water during the summer months. Hence the impact to agriculture, and the accompanying local communities and their economies will be significant.

A week or so ago, on a Sunday afternoon, I flew across Middle America to Colorado for a meeting and was again struck by the crop circles that dominate the landscape west of the Mississippi River. They are everywhere and are a clear sign of unsustainable groundwater use. I recently participated in a fly in event for National Groundwater Association in Washington DC, where several speakers, including myself, talked about dwindling groundwater levels and the impact of agriculture, power and economies. The impact is significant. Dr. Leonard Konikow, a recently retired USGS scientist, noted that he thinks a portion of sea level rise is caused by groundwater running off agriculture and from utilities and making its way to the ocean. He indicated that 5% of SLR each year was caused by groundwater runoff, and has upped his estimates in the past 10 years to 13%. This is because it is far easier for water to runoff the land than seep into rocks, especially deep formations that may take many years to reach the aquifer. And since ET can reach 4 ft below the surface, many of the western, dry, hot areas lose most of this water during the summer months. Hence the impact to agriculture, and the accompanying local communities and their economies will be significant. In the last blog we talked about Flint’s water quality problem being brought on by a political/financial decision, not a public health decision. Well, the news get worse. Flint’s deteriorated water system is a money thing as well – the community has a lot of poverty and high water bills, so they can’t pay for improvements. They are not alone. Utilities all over the country have increasing incidents of breaks, and age related problems. So the real question then is who are the at risk utilities? Who is the next Flint? It would be an interesting exercise to see if a means could be developed to identify those utilities at risk for future crises, so we can monitor them in more detail as a means to avoid such crises.

In the last blog we talked about Flint’s water quality problem being brought on by a political/financial decision, not a public health decision. Well, the news get worse. Flint’s deteriorated water system is a money thing as well – the community has a lot of poverty and high water bills, so they can’t pay for improvements. They are not alone. Utilities all over the country have increasing incidents of breaks, and age related problems. So the real question then is who are the at risk utilities? Who is the next Flint? It would be an interesting exercise to see if a means could be developed to identify those utilities at risk for future crises, so we can monitor them in more detail as a means to avoid such crises.